Write Your Own Bible and Then Try to Live by It

Journal Entry: December 25, 2025 – 6:18 AM

Write Your Own Bible and Then Try to Live by It

Journal Entry: December 25, 2025 – 6:18 AM

The saying is disarming in its simplicity: Write your own bible and then try to live by it. It sounds almost flippant at first, even heretical to some ears. But beneath the surface, it offers a radical invitation, one that quietly rearranges the furniture of responsibility, meaning, and authorship.

To write your own bible is not to declare yourself infallible. It is to acknowledge that, whether you admit it or not, you already live by a text. Everyone does. The question is whether that text has been consciously written or unconsciously absorbed.

Most people inherit their bible piecemeal. In fact, the bible as we know it today is a parred down piecemeal collection of unrelated documents collected over centuries. The personal bible we all live by has been created through family habits, cultural expectations, assumptions, religious instruction, advertising slogans, political myths, social media incentives, and unexamined fears. It is stitched together from rules never fully articulated and values rarely questioned. The result is a doctrine that governs behavior without ever revealing its authorship.

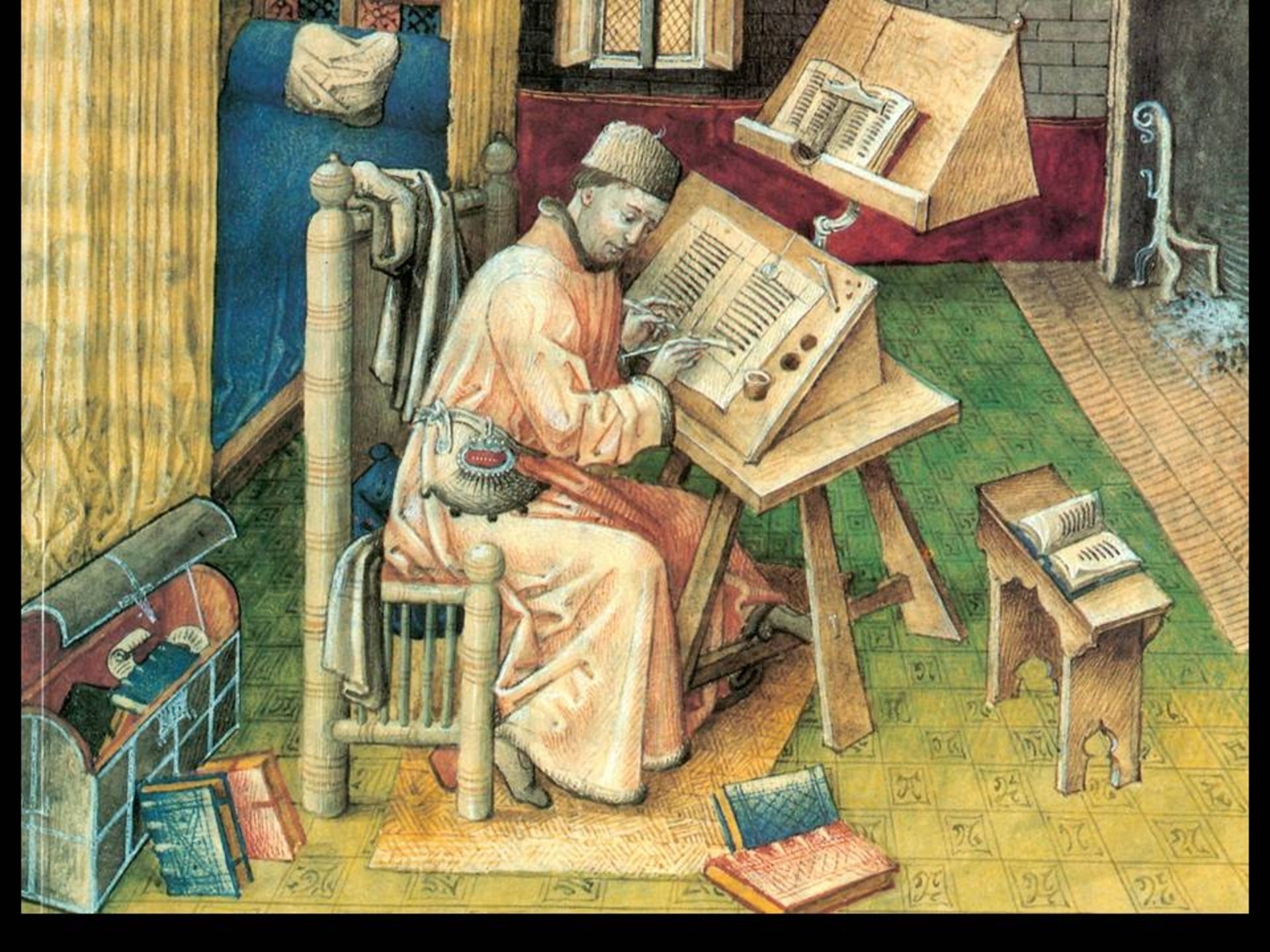

The saying proposes a reversal. Instead of being edited by invisible hands, you become the editor. You sit down and ask: What do I actually believe about how to live? What do I consider sacred? What lines will I not cross, even when it costs me? What virtues am I willing to practice daily, not admire abstractly? What failures am I prepared to own without outsourcing blame?

Writing your own bible does not mean inventing truths out of thin air. It means listening carefully to the truths that have already been shaping you and deciding which deserve a place on the page. Some lines will come from ancient wisdom. Some from hard-earned personal experience. Some from mistakes you would rather forget but cannot honestly exclude. A personal bible is less a proclamation than a reckoning.

Then comes the second half of the saying, and it is the harder half: and then try to live by it.

The word “try” matters. It admits imperfection. It leaves room for growth, contradiction, and revision. A personal bible is not a contract signed in blood. It is a living document, one that evolves as understanding deepens. To try to live by it is to engage in daily practice rather than perform symbolic allegiance.

Living by what you have written exposes the distance between aspiration and habit. It reveals where courage thins out, where convenience overrides conviction, where comfort edits out compassion. This is not failure. This is the point. A personal bible functions like a mirror more than a law book. It reflects who you are becoming, not just who you wish to appear to be.

There is also a quiet ethical consequence to this approach. When you write your own bible, you can no longer hide behind borrowed authority. You cannot say, “I was just following orders,” whether those orders come from tradition, ideology, or trend. Responsibility moves closer to the bone. Your life becomes a footnote to your own text, and every action either clarifies or contradicts what you claim to hold sacred.

For creatives, this idea carries particular weight. Every artist already writes a kind of bible through repetition, through what they return to, through what they refuse to let go. Themes recur. Obsessions persist. Questions echo. To write them consciously is to align practice with purpose. To live by them is to let the work shape the life, not only the portfolio.

The saying does not ask you to discard collective wisdom or shared stories. It asks you to metabolize them. To take what nourishes, discard what deadens, and articulate a code that can be tested in the world rather than admired on a shelf. In this sense, a personal bible is less about belief and more about orientation. It answers the question: In the face of uncertainty, which direction do I turn?

Perhaps the most radical aspect of the saying is its humility. It does not say your bible will save the world. It says it might save you from living unconsciously. And that may be enough. A life lived in honest dialogue with its own principles generates a quiet coherence. Not perfection, not sainthood, but integrity in motion.

Write your own bible. Not to enshrine yourself, but to clarify yourself. Then try, day by day, to live as if your words mattered. Because they already do.

Commonplace Book and Personal Bible: Two Ways of Writing a Life

Journal Entry: December 25, 2025 – 7:24 AM

A commonplace book and a self-written bible sit near one another on the same shelf, but they serve different functions. One gathers. The other commits. Understanding the difference clarifies how a life is shaped through language.

A commonplace book is receptive by nature. It is a vessel for fragments: quotations, observations, overheard phrases, images, questions, and half-formed insights. Its organizing principle is attraction rather than conclusion. You copy something down because it struck you, not because you fully agree with it. The commonplace book does not demand resolution. It allows contradiction to coexist. Over time, patterns emerge, not by decree, but by accumulation.

In this sense, a commonplace book reflects the mind in motion. It honors curiosity. It records influence. It shows what keeps calling for attention across years. Many of its entries are provisional, borrowed, or situational. It is closer to a field notebook than a rulebook. You can open it anywhere and enter a conversation already in progress.

Writing one’s own bible, by contrast, is an act of synthesis and responsibility. It is selective. It asks not only what resonates, but what you are willing to stand behind. Where the commonplace book says, “This is interesting,” the personal bible says, “This matters enough to guide my actions.” It converts insight into orientation.

The relationship between the two is sequential, though not strictly linear. The commonplace book feeds the bible. It is where raw material is collected, tested, and revisited. Many ideas live for years in a commonplace book before they are either discarded or distilled into principle. Without this preparatory space, a personal bible risks becoming brittle, ideological, or prematurely fixed.

The difference is also ethical. A commonplace book carries little obligation. You are free to record something today and forget it tomorrow. A personal bible carries weight. Once written, it implicates you. It invites accountability. It asks whether your choices align with your stated values. It turns reflection into practice.

There is also a difference in voice. A commonplace book is polyphonic. Many minds speak within it. It preserves the echo of teachers, poets, ancestors, strangers, and former selves. A personal bible is written in your own hand, even when it draws from shared wisdom. It does not erase its sources, but it assumes authorship.

One might say the commonplace book is a library, while the personal bible is a compass. The library expands what you can think. The compass helps you decide where to go with that knowledge. Confusing the two leads to imbalance. A life of only commonplacing can become endlessly exploratory without commitment. A life of only commandments can become rigid, closed, and defensive.

At their best, the two remain in dialogue. The commonplace book stays open, porous, and curious. The personal bible stays revisable, humble, and lived. One keeps the self teachable. The other keeps the self answerable.

In practice, many artists, writers, and thinkers move between these modes without naming them. They gather obsessively, then periodically distill. They listen widely, then choose carefully. Seen this way, writing one’s own bible is not a rejection of influence, but the moment when influence becomes integrated.

The commonplace book asks, What am I noticing?

The personal bible asks, What am I willing to live by?

A thoughtful life needs both.

From my understanding, the Bible was written as a means of controlling the masses, at least the King James version was. I feel the rule book that says "Do it this way or die" is not a book about love, it is a book of constraints. To model our own personal Bible after the original, even "loosely", is providing ourselves reasons to succeed or fail. At the time of it's writing, most communities were tribal, where freedoms did not exist, but strong laws were required in order to induce the desired behavior. Personally, I don't desire a rule book to use as guidance, which is limited and inflexible. We are too self limiting as it is. My personal Bible would be panoramic in nature, looking at everything in context to make the best choices for myself, again, fluidity being the key source of personal guidance, which changes often, but then I never was very good at following rules. However, I can say the Christ Consciousness, leads me.

For me, I won't call 'my book' a bible as for me there's only one that was already written using that word. But for me, I'd rather call it just 'my book' or 'my code of ethics or philosophy'. Anyway, other than that, excellent essay(s) here. It's important to know who we are (were and to become), are allowed to edit not the past, but each current moment as we feel is right and to keep critical thinking alive with the ability to open one's eyes, ears, heart, brain to keep on learning, seeing, knowing and not allowing to be influenced by false prophets yet hearing all sides. And we must examine our convictions, the ones we believe are written in stone. Recognizing one's moral compass is always needed, fine tuned, adding and subtracting when necessary. Awareness. Mindfulness. Listening.