I was poking around on the internet and happened onto an article that I completely forgot about. See the whole thing in its original form with images here: poemeleon.me/touchon-spotlight

This is an expanded version of that article.

What inspires you to create asemic texts?

As a child I spent nine years in Catholic private school. That is probably inspiration enough for learning to express oneself in a cryptic, unknowable manner. Who, after all, wants to risk being burned at the stake because their words were misunderstood by the ignorant - or worse, by the institution? I say that jokingly, but as with all such jokes, there is a kernel of truth buried inside. Growing up in that atmosphere instilled in me a double vision: both a fascination with sacred texts and an awareness of how words can be weaponized.

I was enthralled by illuminated manuscripts. The idea that writing could be so precious, so revered, that monks would devote their entire lives to the slow copying, embellishing, and preserving of texts - this left a permanent impression. Those manuscripts were not just books, they were acts of devotion, each letter a prayer, each margin a meditation. The pages glowed not only with pigment and gold but with the sense that human beings had chosen to pour their existence into safeguarding language as a vessel of the sacred.

And yet, even while I admired this, I also grew suspicious of it. Writing and reading, the whole business of knowledge-gathering and preservation, is one of humanity’s strangest peculiarities. Language fascinates me - its ability to crystallize thought, transmit vision, carry inspiration across centuries. But I cannot escape the other side: language’s shadow, its capacity to distort, to mislead, to enforce obedience, to shame, to manipulate, to cajole. With a turn of phrase, one can spark a movement or crush a spirit. With the wrong word, whole lives can be condemned.

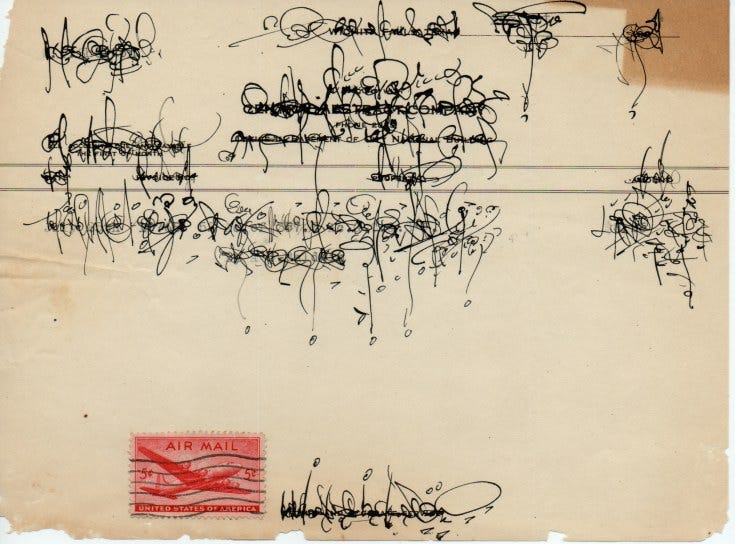

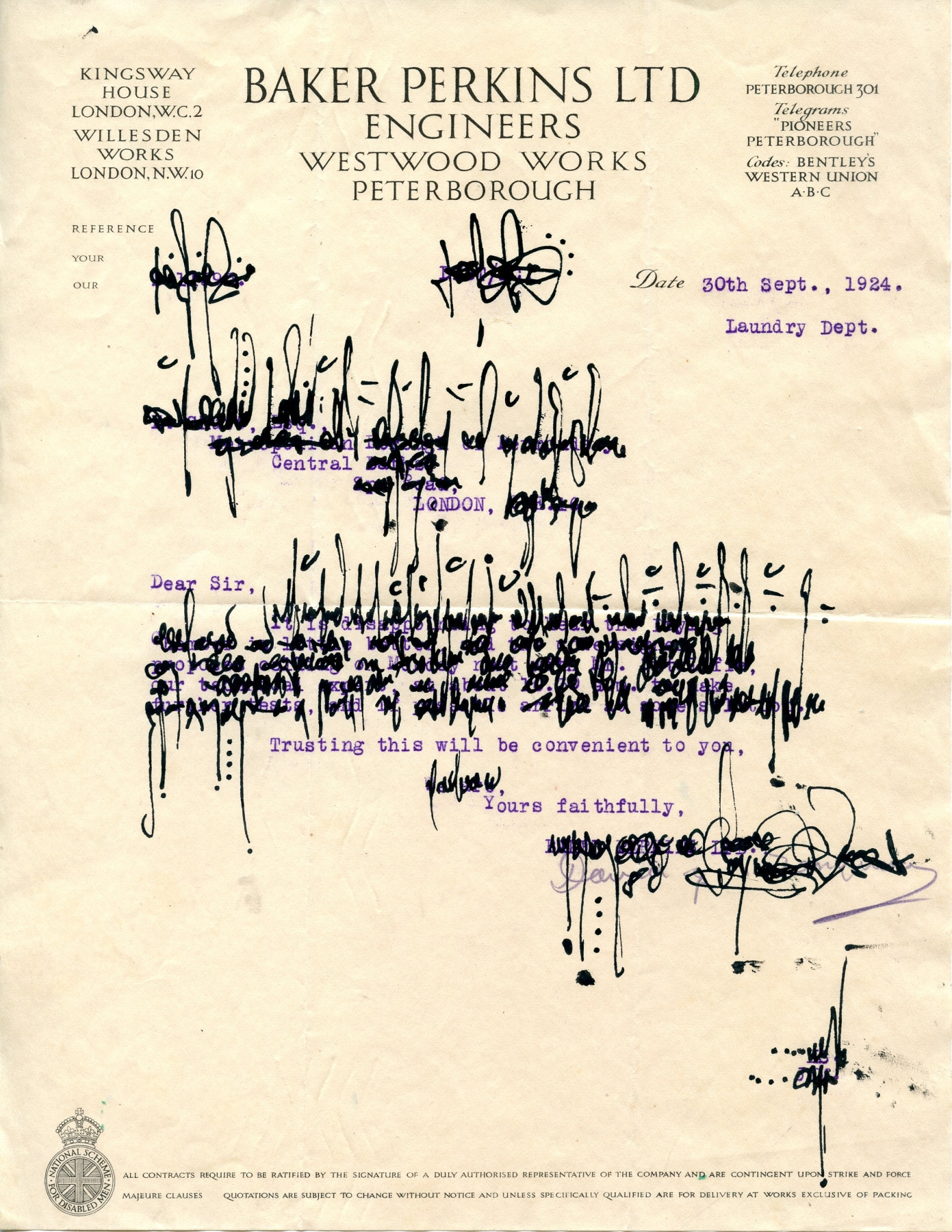

This tension has stayed with me: the shimmering promise of language and its latent danger. Perhaps that is why asemic writing feels so natural to me - it acknowledges both the beauty and the treachery of words. It preserves the gesture of writing while releasing it from the snares of interpretation. It is script without sentence, illumination without doctrine, a space where the hand still testifies but the tribunal of meaning cannot pass judgment.

As a visual artist I often sense a wide gulf between what can be spoken and what cannot, between what is said and what endlessly goes unsaid. Poets are forever working at that threshold, trying to push language to the edge of its own capacity, testing how far words can bend toward silence or the unsayable. My own response, as a collage artist, has been to take language itself apart, to strip away its burden of meaning and reassemble it into something mute, something abstract. In this way I create texts that do not carry messages, and it is precisely in their refusal that they open into another register of experience. They become universalized statements - not of what is said, but of the very fact of saying itself. They remain as patterns, designs, artifacts, physical remnants of human communication without the oppression of meanings that press too heavily on them.

When we encounter a text, most of the time we do not actually see it. We look through it, straight to the meaning embedded inside, as if the letters and shapes were merely transparent carriers. The material fact of the text disappears, vanishes into utility, leaving only the message echoing in the mind. The alphabet, in this sense, is a kind of work animal. The letters are beasts of burden, tethered together into words and sentences, pressed into service to haul meaning on their backs. Their individuality is erased by the yoke of utility. Each one is conscripted into a system, carrying loads from one mind to another, endlessly repeating its task.

There is something wondrous in this. It is miraculous that scratches on a surface can bear such cargo across time and space, transmitting thought, comfort, beauty, knowledge. A single phrase can reach across centuries, bridging lives and cultures. But at the same time there is something deeply tragic in it. The letters themselves are invisible, their lives consumed in service to the message, their presence unacknowledged. It reminds me of workers in a vast machine, their bodies and hours purchased to carry the dreams of someone else’s design. The brilliance of language and its ingenuity is undeniable, yet it comes at the cost of invisibility for the carriers themselves.

Collage and asemic writing offer me a way to free the letters from this servitude. By breaking apart words, scattering fragments, or dissolving the burden of meaning altogether, I allow the letters to stand again in their own right - shapes, marks, gestures, patterns. They are released from obligation, allowed to be visible once more. In this liberated state, they can be appreciated not for what they say but for what they are: artifacts of human presence, traces of hand and voice, mysterious forms that remind us that communication itself is as much about being as it is about meaning.

On the Mystery of Asemic Writing

Asemic writing emerges for me out of the mark-making tradition, that primal impulse to leave traces, scratches, or gestures behind. Collage, my other primary medium, works by bringing fragments of the world into juxtaposition. Asemic writing, by contrast, begins with nothing but the hand, the body, the page. What it records is not content but gesture: the body language of writing. In this way it feels more like playing a musical instrument. Each mark is a note, each line a phrase, each page an improvisation in visual rhythm. Except instead of sound, the record is ink and stain, fossilized motion on paper.

When I practice, I watch my own impulses with the same attention I might bring to meditation. A movement arises, I follow it, I break it, I repeat it. Sometimes I find myself searching for flow, other times for disruption. I invent new abstract vocabularies, sometimes disciplined, sometimes erratic. The tools themselves shape the language: a frayed brush opens into feathered line; a stick dipped in ink leaves hesitant stutters; liquids pool, bleed, resist. Each session becomes a small experiment in what can happen when intention and accident conspire together.

Yet the persistent question hovers: Why make asemic work at all? Why me, and why so many others across the world, independently drawn into this strange, wordless writing? My answers are provisional, never final. At best, I gather possibilities.

One answer may be historical. Asemic writing can be seen as the continuation of abstraction into the last bastion of representation: language. In the twentieth century, painting shed the duty of depiction, sculpture abandoned the figure, music drifted from harmony into texture and pure sound. Language has been slower to yield, still burdened with meaning, still tethered to its utilitarian function. Asemic writing severs that tether. In this it joins artists like Henri Michaux, whose ink drawings resembled alphabets from an undiscovered civilization; Brion Gysin, whose cut-up experiments with language blurred sense and nonsense; and Cy Twombly, whose scrawls hover between script and scribble, ancient graffiti and lyrical notation. In China, Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky carried this impulse into monumental form, printing entire volumes of invented characters, every page legible in form yet unreadable in content.

Another answer may be cultural. We are shifting from a literate to a post-literate age. Once, print culture shaped consciousness itself; now, screens flood us with images, icons, fragments of text. Communication is increasingly visual, atmospheric, hybrid. In this environment, asemic practice feels less like an art-historical experiment and more like an evolutionary rehearsal: a way of writing beyond writing, of preparing for a world where the boundaries between text and image have dissolved.

There is also the mystical answer. Across traditions, writing has carried a sacred charge. Islamic calligraphy, stripped of figural image, made the written word itself an art of devotion. Kabbalistic texts saw letters as primal forces, each one alive with divine energy. Sufi mystics spoke of khatt, the line, as a trace of spirit. Even medieval marginalia - those playful, excessive doodles in illuminated manuscripts - remind us that the hand wanders where the mind cannot always follow. Asemic writing stands in this lineage, though its prayer is stripped of words. It is the gesture of invocation without dogma, a silent liturgy of marks.

And then there is the more surreal explanation. Perhaps asemic writing is a kind of virus, a contagious form of automatic writing released into the world. Like the Surrealists, who trusted the unconscious hand to bypass rational thought, asemic writers today let the hand slip free of meaning, discovering forms that arrive as if from elsewhere. There is a dreamlike contagion in this, a sense that the marks themselves want to proliferate, independent of our intentions.

Yet beneath all these explanations lies a deeper one. Asemic writing is, at heart, a response to awe. The universe is too vast, human culture too intricate, the mystery of being too profound for words to encompass. Language, brilliant as it is, collapses under the weight of existence. We are left speechless. But the hand does not stay still. It moves, compelled to leave a testimony even when nothing can be said. The page fills with traces: mute yet eloquent, silent yet insistent.

In this way, asemic writing does not escape language so much as return to its origin. Before alphabets, there were scratches on bone, ritual marks on stone, glyphs whose meaning was never fixed but always lived in gesture, ritual, presence. Asemic practice may be the contemporary echo of that impulse. Not a message to be decoded, but a sign that we are here: living, witnessing, inscribing what cannot be spoken.

This is beautifully articulated. I appreciate how you capture the tension between language as a tool for connection and as something that can also distort or confine. The way you describe asemic writing as honoring the act of writing itself, beyond meaning, really struck me. Thanks for sharing your perspective; it makes me see both language and art in a new light.

I've long found your asemic (a new word for me) drawing to be particularly beautiful. Now I have some understanding of why. A beautiful, beautiful line of thought.