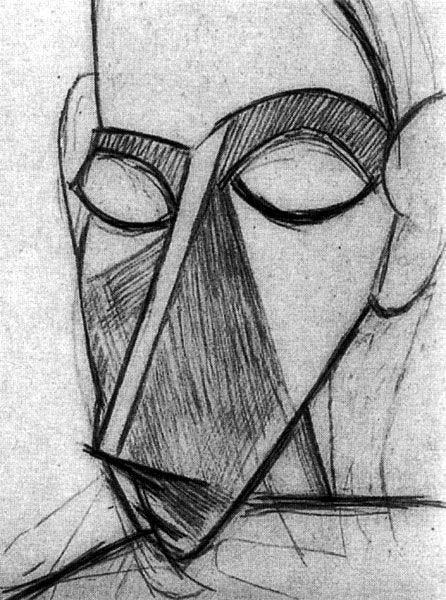

Here is a little painting I made in 2017 based on a small sketch by Pablo Picasso (below). I call it ‘Woman with a Plane Face” As a young artist in the early 1970’s I was coming into the art world at a time when a lot of the legendary artists of the early 20th century were still alive and working so I was a lot closer to this history at that time compared to now when it just seems like a part of the remote, misty past. But for me it continues to reverberate and be of interest.

Cubism had a profound influence on both the Russian Avant-Garde and Italian Futurism, significantly shaping their aesthetics and artistic philosophies. The movement’s radical approach to form, perspective, and representation opened new avenues for artists to explore abstraction and the breakdown of traditional visual conventions. Both the Russian and Italian movements absorbed Cubist techniques, while also adapting them to express their own unique cultural and ideological goals.

Influence on the Russian Avant-Garde

The Russian Avant-Garde was a broad, innovative movement that encompassed various styles and groups, including Suprematism, Constructivism, and Rayonism. Artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, and Natalia Goncharova drew on Cubist principles, using geometric abstraction to explore themes of modernity, industrial progress, and the pursuit of a utopian future.

Cubism’s analytical deconstruction of objects resonated with Russian artists, particularly Malevich, who saw in Cubism a pathway toward total abstraction. Initially influenced by both Cubism and Italian Futurism Malevich developed what can be called Cubo-Futurism.

The work of mine below is based on Malevich’s "The Knife Grinder" (1912-1913) which demonstrates the Cubist influence in its fragmented depiction of a man with a mustache wearing a hat sitting next to a stair case with rounded treads peddling a grinding stone while grinding a knife. The image dissects the form into sharp, angular planes, reflecting the Cubist approach of breaking down objects into geometric shapes, while also hinting at the dynamic motion of grinding a knife characteristic of Futurism.

This is one of my ‘New and Improved Modernist Masterworks’ paintings. I occasionally have made over the years of my own version of favorite modernist paintings so that I, through the act of making the painting, am forced to spend a great deal of time studying a specific work to see how it was made, analyze the color scheme, the composition, the light, the space, etc. The original painting by Malevich is about 31 x 31 inches. My version is 60 x 60 inches.

I once rented a studio space in Fort Worth, Texas around 2005-6 that had previously been used by a carpenter and he has left behind very large work bench and a lovely 5 x 5 ft. sheet of 1/4 inch birch panel so I used it to make this painting. I worked on it here and there as I had time and drug it around with me from studio to studio over a few years and eventually had the cradle built for it so it could hang on the wall. I made a few ‘improvements’ in the image aside from the significant increase in size. Hence it is ‘new and improved’. My theory is that the early 20th century painters were beginners as far as the new forms of painting they were pioneering and that us painters several generations down the trail know a lot more in retrospect than they did about what they were doing.

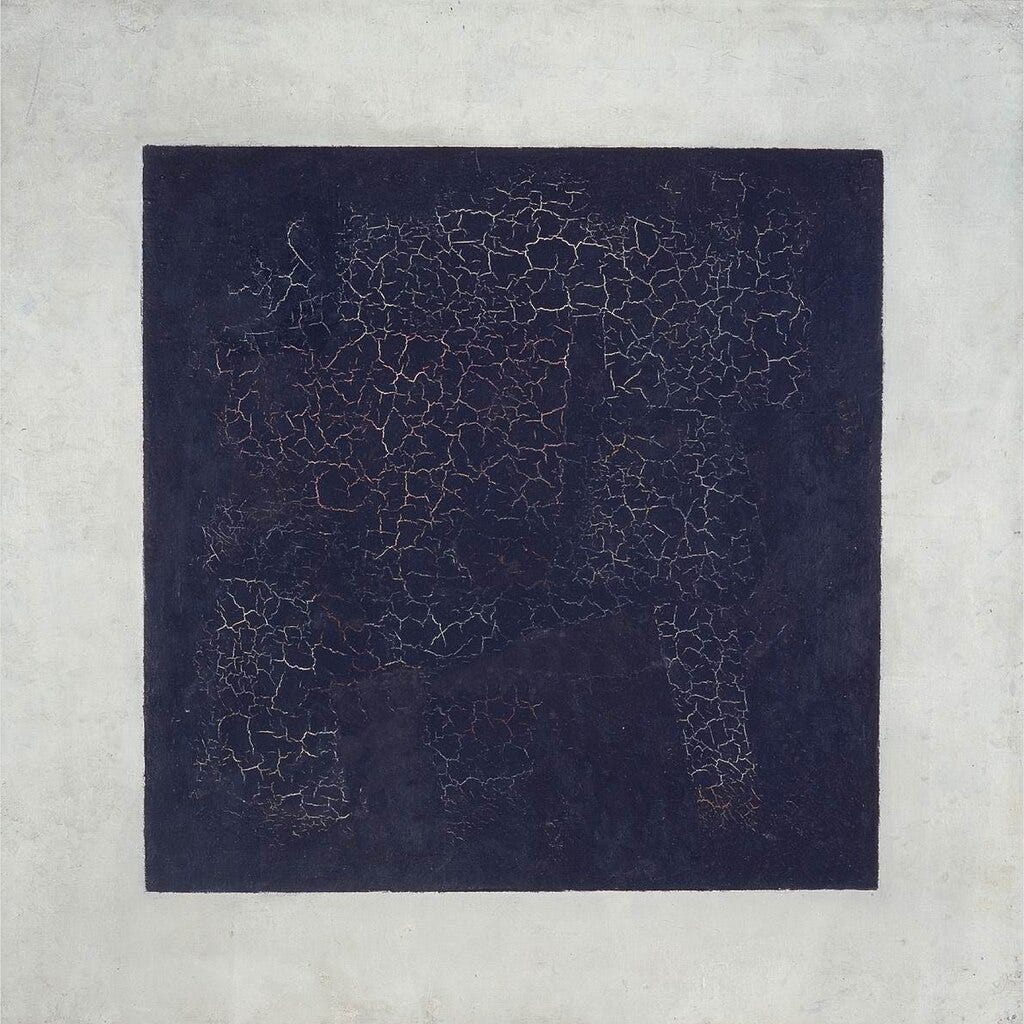

Malevich quickly moved beyond Cubo-Futurism to develop Suprematism, an art movement focused on pure abstraction and the supremacy of geometric forms. His work “Black Square” (1915) represents a culmination of Cubist influences, distilling form to its most basic essence and marking a radical break from representational art. My favorite part in this painting and many of Mondrian’s paintings are the organic cracks in the paint. I love that.

Vladimir Tatlin, a central figure in the Constructivist movement, was deeply influenced by Cubist techniques and materials. During his time in Paris, he encountered the works of Picasso and was inspired by his use of everyday materials and collage. Tatlin’s famous “corner counter-reliefs”—three-dimensional constructions made from metal, wood, and glass—show a clear connection to the Cubist interest in merging painting with sculpture. His work laid the foundation for Constructivism, an art movement that sought to integrate artistic practice with industrial production and emphasize utilitarian forms.

Lyubov Popova and other Russian artists developed what they called "Cubist-Futurism," which combined the fragmented forms of Cubism with a sense of dynamism or visually representing movement. Popova's paintings, such as "The Traveler" (1915), reflect her engagement with Cubist geometry and her interest in exploring space and movement.

This abstracted composition suggests the speed and sense of dislocation associated with modern transport, and seems to include an oblique self-portrait in the central figure: a woman wearing a yellow necklace and high-collared cape who reads a magazine or newspaper in her seat on a train, grasping a green umbrella in one gloved hand. Snatches of words (including the Russian terms for “gazette,” “hat,” “2nd class,” and the roar of the train) vividly convey the sights and sounds of locomotive travel. With her use of found text, fragmented forms, and shapes rhythmically repeated to create a sense of acceleration.

Popova produced a number of paintings in her tragically brief life that were of interest to me. I have studied this particular painting in person on two occasions over the years at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California - a favorite painting.

Influence on Italian Futurism

Italian Futurism, founded in 1909 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, sought to capture the energy and dynamism of the modern industrial age, celebrating speed, technology, and the violent rupture with tradition. The Cubist emphasis on fragmentation and multiple perspectives provided Futurist artists with the tools to depict movement and the sensation of simultaneity in their work.

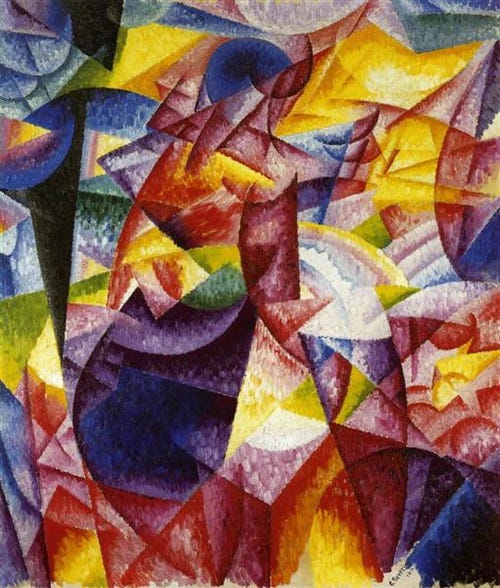

Gino Severini, Umberto Boccioni, and Carlo Carrà were among the key figures of the Italian Futurist movement who incorporated Cubist techniques into their paintings. Cubism’s breaking apart of objects into geometric shapes allowed the Futurists to convey the concept of time and space as fluid and interconnected. In Severini’s work “Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin” (1912), the influence of Cubism is evident in the fractured forms and overlapping planes, used to convey the vibrant, pulsating atmosphere of a Parisian dance hall.

Umberto Boccioni, another prominent Futurist, was heavily inspired by Cubism’s abstract language but adapted it to express a heightened sense of dynamism and emotional intensity. His paintings, such as “The City Rises” (1910), and sculptures, such as “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space” (1913), demonstrate a Cubist-inspired fragmentation of form, combined with sweeping lines that suggest rapid motion and fluidity. Boccioni's aim was not just to deconstruct objects but to capture the energy and transformation inherent in modern life—a vision that aligned with the Futurist celebration of technological progress and velocity.

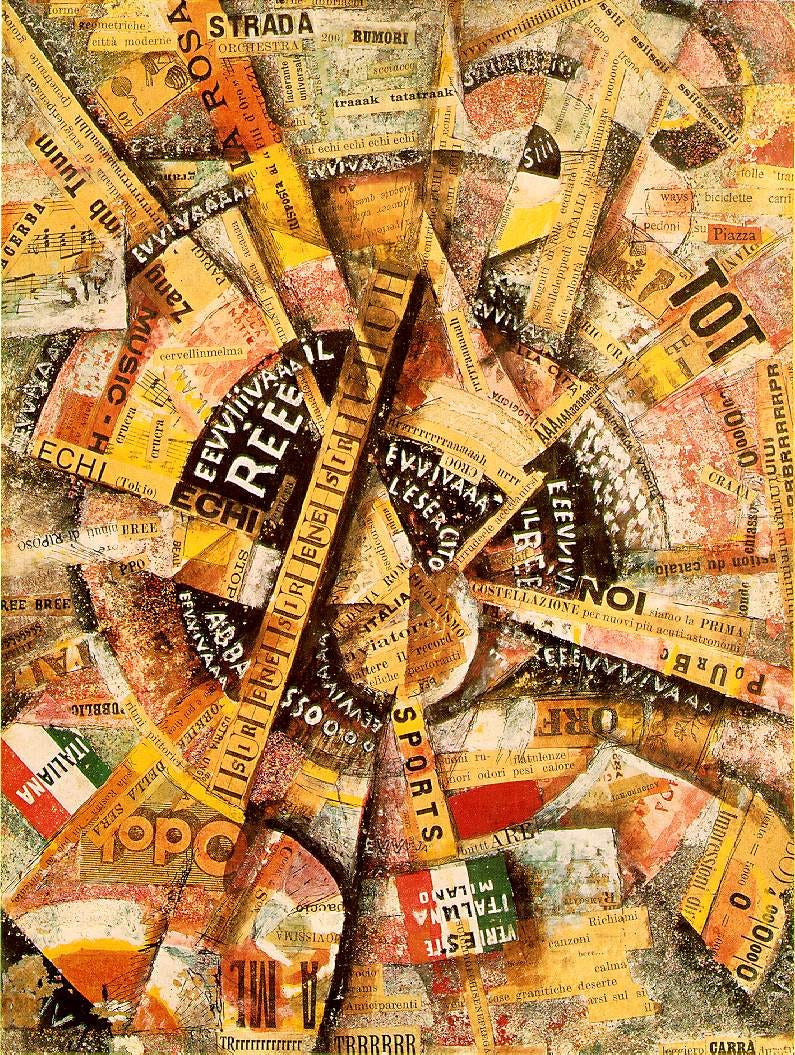

The influence of Cubism also led the Futurists to experiment with collage and mixed media, drawing inspiration from the Synthetic Cubism of Picasso and Braque. This allowed them to incorporate elements of mass culture, such as typography and mechanical imagery, further emphasizing their alignment with industrial modernity. Carrà’s use of fragmented imagery and bold, angular forms reflects the Cubist deconstruction of reality, while also injecting the dynamism and movement central to the Futurist agenda.

Distinct Adaptations

While both the Russian Avant-Garde and Italian Futurism drew heavily from Cubism, they each adapted the style to fit their distinct ideologies and artistic goals. The Russian Avant-Garde was largely driven by a desire to redefine art in the context of social transformation and collective progress, particularly in the wake of the Russian Revolution. Cubism provided the tools for these artists to break free from realism and embrace abstraction as a means of envisioning a new society.

Italian Futurism, on the other hand, sought to glorify the present, celebrate industrial progress, and provoke through its association with speed, violence, and technology. The adaptation of Cubist fragmentation by the Futurists aimed at capturing motion, energy, and the sensory experience of modern urban life, often with a nationalist and confrontational undertone.

Most of my ideas of visual musicality are deeply informed by the work of these early painters. Back in the 20th century it took a long time to start sorting out this revolution in painting from an academic and art historical point of view. It is still being sorted out even today. In my case, as an artist, a lot of the articles I will be presenting in the coming months could not have been explored without the internet.

As an artist, who remembers the dark ages before the rise of the internet, I am deeply appreciative of my ability to be able to explore these ideas from the comfort of my own studio.

Nice to see your drawing and a lot of old favorites. First time we went to the Picasso museum I was thinking it was just to say we went, but we ended up going many times, and being awed by the variety and ground breaking work. And I do love Russian constructivism.

Thanks for this info about the influence.

I found this really interesting and learnt a lot. Thank you! And I love your painting inspired by the Malevich.

I was very interested by your point that the resources of techniques like cubism were by no means exhausted - or even fully understood - by the early practitioners. Your remark reminds me of something TS Eliot said about past masters. From memory, he said "we know more than them and they are what we know."