I started to write a response to Matthew Rose’s comment related to:

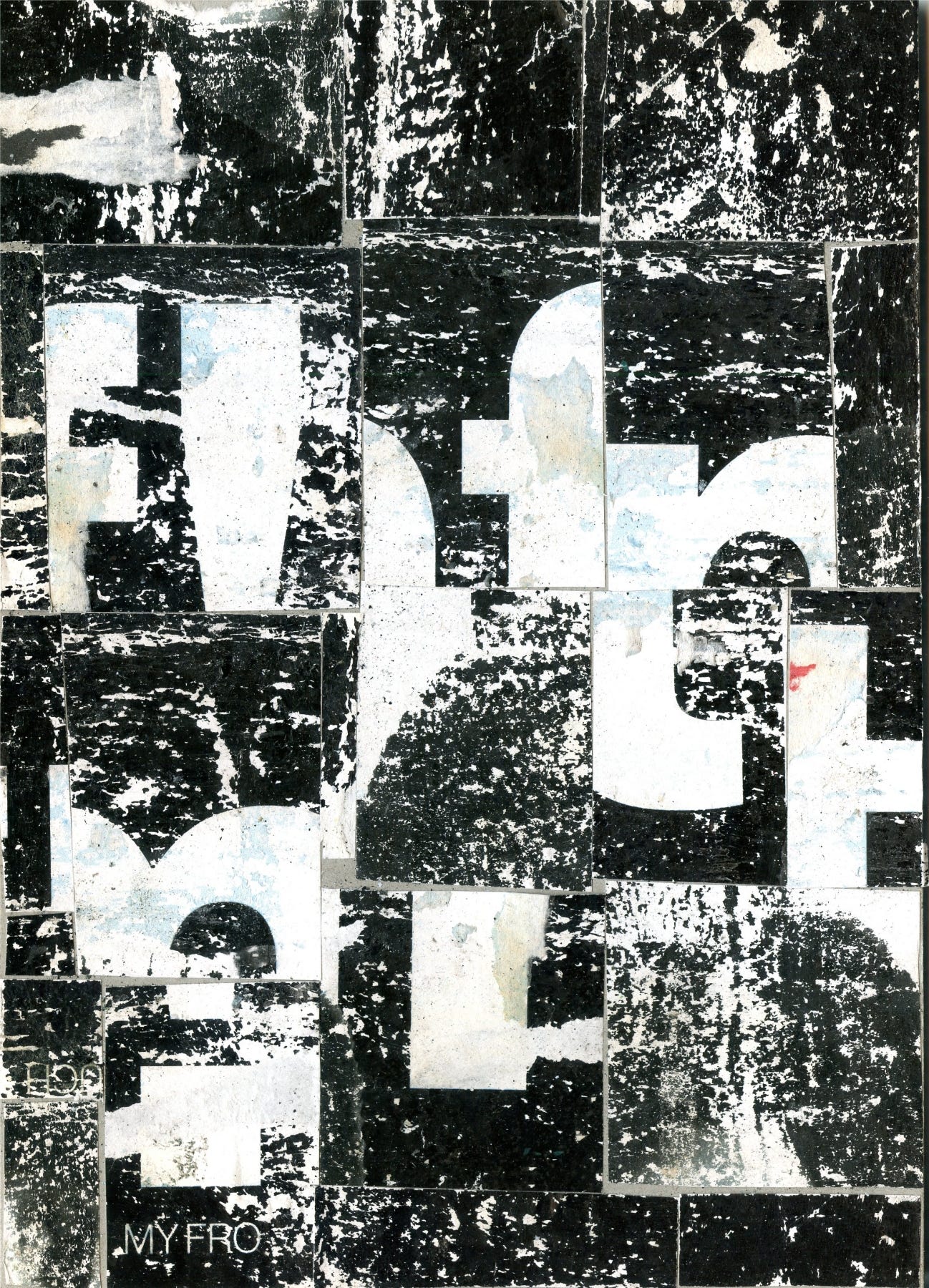

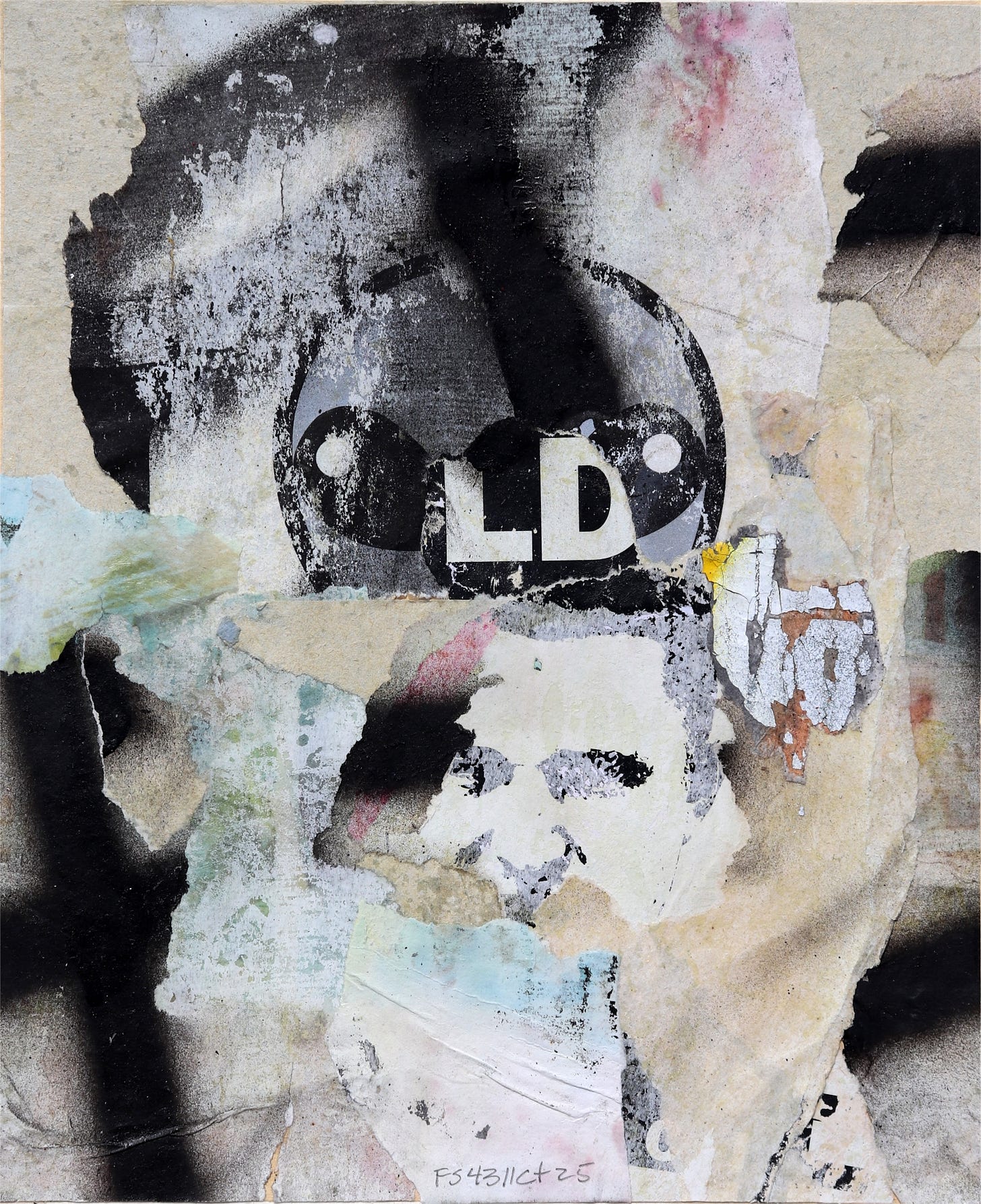

Cecil, when you write: “And I came to see this practice as more than just a visual strategy. It became a kind of philosophy of attention. A way of engaging equally the negative and positive spaces and shifting them back and forth and using texture and color and form and composition as a painter would do - pulling the type out of the land of utility and into painterly culture.”

You are indicating a breakthrough attributed to Jasper Johns, who painted FLAG in 1954-1955. The encaustic painting straddled the fence of being a flag and a representation of a flag. Johns said the painting was something “the mind already knows.” This is perhaps what you refer to when you cite “utility” (meaning the use of the flag as a national or regional symbol of something) and artifice (painted representation). In that there is tension and something significant about how we perceive reality, or as you put it, a philosophy of attention.

But I soon calculated that I should flesh it out into an article. so here you go…

The Land of Utility

When we speak of “the land of utility” in relation to letters and fonts, we are describing a realm where form is subordinated to function. In this land, letters are servants, bound to carry messages from sender to receiver. Typography is pressed into service for advertising, announcements, signage, contracts, political propaganda. Its measure of success is efficiency: did it communicate clearly, quickly, without confusion? Did it mean exactly what it was meant to mean and not something else? In this sense, the designer’s task is not to explore the being of the letter but to erase its strangeness so that meaning flows smoothly across its surface into the mind. The letter becomes transparent, a vessel emptied of its own aesthetic weight in order to bear a client’s cargo.

Beyond Utility: The Letter as Being

To step outside this land is to return the letter to itself. Here, the ‘A’ is not a conveyor but an autonomous shape, as natural and irreducible as a flower petal or a stone. Its angles, curves, densities exist apart from any directive to “say something.” This shift reclaims letters as presences rather than servants, as entities that can occupy space, resonate visually, or stand in silence without explanation. In such a space, typography is no longer a medium for message but an event of raw seeing.

Parallel with Abstract Painting

This mirrors the revolution in abstract painting. For centuries, painting was tethered to representation: religious scenes, portraits, landscapes, allegories. The painted surface was a window onto something else, and its value was measured in mimetics: fidelity to story or likeness. With abstraction, the surface itself became the subject. Paint was freed from obligation to illustrate, and instead was allowed to exist as paint—color, texture, rhythm, gesture. What was once subordinate became primary. The non-utilitarian, non-representational dimension of painting came into its own.

Toward an Autonomous Aesthetic

In this light, both abstract painting and the non-utilitarian use of typography share a refusal of servitude. They propose that art need not be justified by what it communicates, depicts, or sells. Instead, they insist on the dignity of presence, the autonomy of form. A letter, like a brushstroke, does not need to “mean” anything in order to matter. It matters because it is. And in that recognition, we are invited to inhabit a world where things are not exhausted by their functions but are allowed to live, radiant and unnecessary, like flowers, like rocks.

The Image Crisis and the Birth of Abstraction

Abstraction did not emerge in a vacuum. It was born from a crisis. With the rise of photography and mechanical reproduction in the nineteenth century, the painter’s age-old role as image-maker was rendered redundant. Why labor over likeness when a machine could capture it with greater speed and accuracy? What once was the painter’s burden—to translate the world into faithful image—suddenly seemed obsolete.

But in this very displacement, a new freedom opened. Painters no longer needed to justify themselves as mirrors of external reality. They were released, however uncomfortably, into a space where painting could confront its own materiality. Out of this crisis grew the revolutions of abstraction: Kandinsky’s resonance, Malevich’s zero point, Mondrian’s grids, Pollock’s drips. Each, in their way, discovered that the end of representation was not an end at all but the beginning of painting as an autonomous act of contemplation.

AI and the Post-Labor Parallel

We stand today in a similar threshold moment. The arrival of AI has begun to take over the rote, functional, and utility-driven aspects of human creativity: drafting, designing, composing, imitating. Just as photography undercut the necessity of painted likeness, AI undercuts the necessity of human labor in its most mechanical forms. The land of utility, once guarded by designers, typographers, and copyists, is now being steadily occupied by machines that perform those tasks with tireless efficiency.

This generates both anxiety and possibility. The anxiety is familiar: a fear of redundancy, of the human hand made unnecessary. But so is the possibility: a chance to be liberated from roles defined by utility and pushed toward terrains where only the human imagination, sensitivity, and contemplative depth can operate.

Toward a Deeper Human Vocation

If the painter’s liberation from the duty of likeness led to abstraction, perhaps our liberation from the duty of utility can lead to a new contemplative order of creativity. Freed from mechanical demands, we may find ourselves re-anchored in domains that machines cannot occupy: the slow rhythms of attention, the cultivation of presence, the pursuit of mystery. These are not “tasks” to be automated but dimensions of being that call forth uniquely human responses.

In this sense, AI is not only an intruder but a midwife. It pushes us, however uncomfortably, toward recognizing that the core of art—and perhaps of human vocation itself—is not in laboring for function, but in opening new vistas of perception, connection, and imagination. The post-labor horizon is not the end of creativity, but the clearing of ground for its deepest flowering.

New Vistas Beyond Utility

If abstraction was the painter’s response to the crisis of the image, then what comes next will be our response to the crisis of labor itself. The creative horizons of the coming decades may no longer be shaped by the need to “be useful or make something useful” but by the discovery of what it means to dwell, to sense, to imagine in ways untethered from utility. Why should any human have to work in a corporate factory when machines will suffice? Several vistas suggest themselves.

1. The Return to Presence

As machines become expert at producing polished outcomes, artists may turn to what cannot be outsourced: presence itself and the creative response. The event of being-with—a performance, a ritual, a gathering, a work created in real time and space—will matter more than the artifacts left behind. Art will be less about the “product” and more about the lived resonance between beings, a return to art as shared atmosphere.

2. The Ecology of Attention

In a world saturated with automated production, attention itself becomes sacred. Artists will learn to cultivate new forms of attention—slow, patient, multi-sensory—and to craft environments that train perception. The gallery may become less a display of objects than a garden for consciousness, a space where people rediscover their own capacity to notice, to breathe, to attune.

3. Imaginal Worlds and Deep Mythologies

If utility-driven tasks are handed over to AI, humans may reclaim the mythic, symbolic, and imaginal. The future may see a flowering of constructed mythologies, immersive narrative worlds, and symbolic systems that reach beyond surface entertainment into the shaping of new cultural imaginations. Where machines generate infinite variations, humans may become the stewards of meaning, weaving together coherence from the flood of possibility.

4. Integration with the Natural World

Artists may also turn toward the more-than-human world, finding in the rhythms of rivers, stones, forests, and skies the inexhaustible sources of form and wisdom. Art might re-enter partnership with ecology, not as a resource to be exploited but as a co-creative partner. Installations might grow like gardens, sculptures might erode like cliffs, performances might follow lunar or tidal cycles.

5. Art as Contemplative Practice

Perhaps most profoundly, art will increasingly resemble meditation, prayer, or philosophy in action. With utility stripped away, the making of art will reveal itself as a way of asking questions no machine can answer: Who are we? What is beauty? How do we belong to this world? The artist will become less a producer of commodities and more a guide into states of mind and heart that awaken the depths of being human.

The Uncomfortable Liberation

This future is not without its tensions. Just as early abstract painters were ridiculed for producing “nothing recognizable,” tomorrow’s artists may be accused of producing “nothing useful.” But this accusation will only confirm that the land of utility is being left behind. What lies ahead is a landscape where art reclaims its primal role: not to serve, not to sell, but to reveal, to point toward a new way of being that will, at the same time, return humanity to an ancient way of being, a more natural way of being. Nature itself will become our guide and our inspiration.

In this new terrain, artists will not compete with machines. They will instead explore what it means to be human in a post-labor world, not a post-work world. All artists love to work, creating works that are not reducible to function but are invitations to contemplation, wonder, and belonging. Eventually everyone will practice some form of art in the new creative society.

You really explained your concept of the (un)function of abstract art, in this case the liberation of word forms to a reasonable argument supporting the underlying scaffolding of shape and space. The "backside" is as important as a liberation of expression as the front side, which shows us where to look, and how to look for all opportunities to experience how the art is "senseless to sense", "Yin to Yang", "form and function", leaning toward "rounded" cubisim but embracing the concept of 3D in the 2D format. This fills in the shape of emptiness to create form. Great job.