Small Work, The Long View

Working small allows you to stay in motion. A piece can begin and end in a single sitting. Decisions happen quickly enough that intuition stays engaged. You can try something, see what happens, adjust, or discard without drama. The feedback loop is short. Learning accelerates.

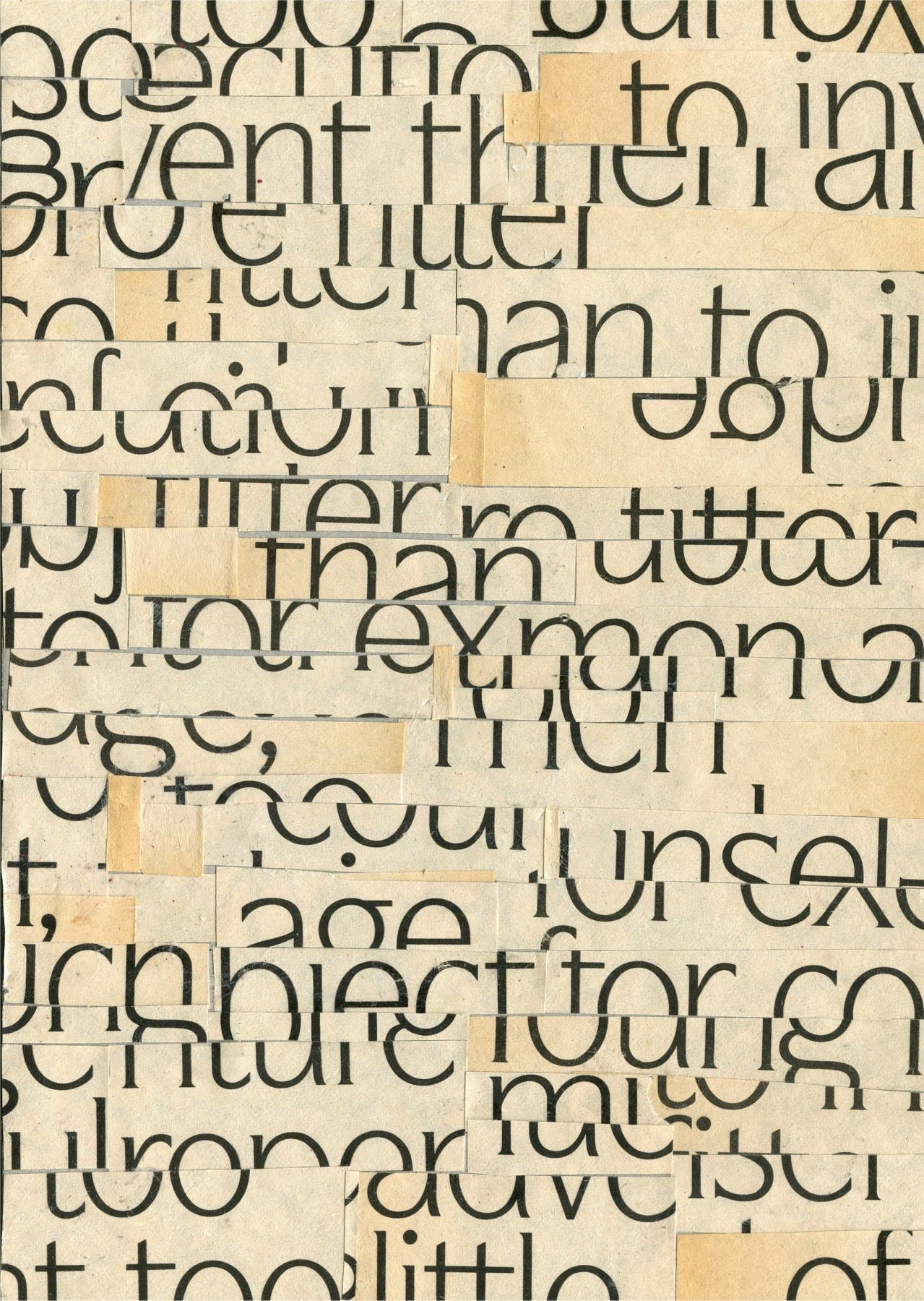

In collage, continuity often does not come from subject matter or intention in the usual sense. It comes from material lineage. A collage artist gathers a body of materials that already share a visual language, paper stock, printing method, typographic voice, era, or emotional temperature. Once those materials are in play, they carry their own internal logic forward from piece to piece.

When the same material appears across multiple works, the pieces begin to speak to one another automatically. They share a history. Repeated fragments become familiar, but not inert. They accrue meaning through reappearance. The suite coheres not because it was planned as a series, but because the material itself enforces continuity.

This is a fundamentally different logic from stand-alone, sporadic works. In those cases, each piece often begins with a fresh material grab, a new visual vocabulary, a reset of context. There is no carried memory. Whatever coherence exists must be constructed from scratch each time, which is much harder to sustain perceptually.

In material-led series, the artist is not forcing unity. Unity emerges. The repetition is not redundancy, it is resonance. Decisions made in one work echo forward into the next. Questions raised by a fragment in one collage quietly continue their inquiry elsewhere. Meaning accumulates through reuse and variation rather than declaration.

This is why such practices feel accumulative rather than episodic. The works are not episodes in the sense of isolated events. They are more like chapters written with the same alphabet, or conversations conducted in the same room over time. The continuity is embedded in the material itself, not imposed conceptually after the fact.

Thinking in terms of suites of works, the process becomes accumulative rather than a sequence of isolated fresh starts. Materials carry their own history forward. When the same fragments reappear across multiple works, they hold the suite together through repetition, memory, and internal logic. Working this way, an artist does not depend on each individual work as a standalone statement but as a part of a suite of works that, taken together, form a whole. This is where the long view begins.

When you make hundreds, then thousands, of small works, you stop expecting any single piece to carry the full weight of meaning. Importance shifts from the individual object to the field they create together. Patterns emerge across time. Themes repeat, mutate, and dissolve. The work begins to speak in a plural voice.

Small work also changes your relationship to risk. Because the investment in any one piece is modest, you are more willing to follow uncertain impulses. You are less tempted to protect the work from failure. This openness is not carelessness. It is curiosity. And curiosity, sustained over long periods, is one of the most reliable engines of growth.

There is a practical dimension to this as well. Small work fits into real lives. It can be made in limited space, with limited time, under imperfect conditions. It travels. It tolerates interruption. This makes continuity possible in ways that large, resource-intensive projects often do not.

For collage artists in particular, small work aligns naturally with the material. Paper fragments invite close attention. The hand and eye operate at a human scale. The work asks to be approached rather than confronted. This intimacy encourages looking rather than scanning.

Over years, the accumulation of small works becomes an archive of thinking. You can trace the evolution of your attention. You can see where you stayed too long, where you moved on too quickly, where something unresolved kept returning. This archive is not just a record. It is a resource. Older work becomes material for new work. The past stays active.

The long view is not about patience as endurance. It is about designing a practice that can continue without strain. Small work makes this possible by lowering the threshold for beginning and reducing the cost of continuation.

There may come a time when larger work becomes necessary or desirable. For many artists, it does. But when that happens, the small work does not disappear. It functions as research, as score, as rehearsal. It feeds the larger gestures with a depth of attention that cannot be rushed.

Working small over a long time teaches you something essential: that significance is cumulative. It accrues through steady engagement rather than singular ambition.

The long view is built one small piece at a time.

And when you look back after many years, you realize that what once seemed modest has quietly become substantial, not through scale, but through persistence.

Yes! Excellent article. This is what I learned when I first was laid off from work into retirement. I had time on my hands. Lots. Of. Times. So I started to make necklaces until that bored me. I hadn't done any assemblage in a long while. So I started with these little pieces and lovingly called them "Shit on Stones". They were these inch high little assemblages. I still have the original 26 of them. From there I went a little bigger, then grew taller/bigger ones until I got back to the size I typically work with. In a way these little pieces were like the finger exercises a pianist would do for warm up. I was slowly putting in 'the big toe' into the cold waters to see if I still "Had It" as I wasn't so sure. Not only did I find I did indeed Have it, but new and improved, better than ever, found confidence, found my art voice, found talents I didn't know I owned. I still love the little works and may do more eventually just because.

Excellent article. This one really speaks to my practice. I enjoy how coherence begins to build all on its own across dozens, then hundreds of small works.