I have been working on a exhibition/installation/catalog idea called The Exquisite Family Records and Archive inspired by the surrealist game The Exquisite Corpse. I dreamed up this idea about 20 years ago. Now that we have ChatGPT I have been working more fervently on the idea and expanding on it.

I have been using old black and white photographs and memorabilia to dream up fictional characters and stories about them. I bought all of these photos and paper artifacts on Ebay - sometimes in lots of a thousand photos unseen, also in thrift stores and antique shops, garage sales, etc. over the last 30+ years. Occasional other ephemera are included. One thing I got in this way, unknown to me when I bought it as part of other ephemera, was the above paper artifact with many signatures on it.

Under the Shadow: A Personal Reflection on the Atomic Age

Pulling out and inspecting various bits of ephemera I pulled out a small, faded piece of paper in my drawer. It's actually in very good condition, it has no creases in it from having never been folded. It looks like it had once been damp because some signatures with the ink in blue blurred a bit. On it are about 22 signatures, scrawled in wartime ink: naval officers, commanders, men of Task Group 1.5, Joint Task Force One. The heading reads "Operation Crossroads, Bikini-Kwajalein, 1946."

A 'short snorter' they call it.

Once a light-hearted tradition among aircrews and military personnel, passed around like a good-luck charm or a receipt of camaraderie. You signed it if you were there, if you belonged. But this one isn't from a bar or a transport plane. It's from the edge of apocalypse. These men were there to witness the first peacetime detonation of atomic bombs, to measure the effects of splitting the world open again. They didn’t drop the bombs on cities this time. They dropped them on ghost ships and fish while the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) were in Japan conducting a long-term study of the health effects on victims and the environment from the atomic bombings.

"Short Snorter from the Edge of the World"

Operation Crossroads, 1946 — Bikini Atoll

This signed document—casually inked by officers of Task Group 1.5, Joint Task Force One—is more than a souvenir of war’s aftermath. It is a silent witness to the moment the world changed.

But what they signed their names to was something far larger. The beginning of the Atomic Age. The quiet hum of annihilation that has never really stopped since.

Passed hand to hand among men stationed on a sunlit atoll in the Marshall Islands, this “short snorter” commemorates their presence during Operation Crossroads, the United States' first nuclear tests after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Their signatures—Lt. Cmdr. Harry W. Lentz, Capt. Edward J. Moran Jr., and others—float like driftwood on the surface of history, while below them, entire worlds cracked open.

Here was fellowship beneath mushroom clouds. A soldier’s tradition transformed into something stranger: a memento not of conquest, but of unleashing the unknowable, the unimaginable and the unacceptable.

The paper resonates with the tremble of fallout and forced exile. While these men etched their names, the islanders of Bikini Atoll were evacuated, their paradise turned into a crucible of radioactive ambition. In this way, the short snorter becomes a cultural artifact of paradox—a document of unity and dislocation, pride and peril.

To hold this item is to press one’s palm against the membrane of history and feel the heat of a new era rising. It is the quiet kind of power: not explosive, but implicating.

Signed at the edge of innocence. Preserved in the shadow of aftermath.

I was born one decade later in 1956. Grade school, early 1960s during the cuban missile crisis. I was 7 years old. We practiced duck-and-cover drills beneath our desks, as if a thermonuclear weapon could be outwitted by hiding under school desks and posture. We were told to stay away from the windows, because the glass would shatter inward from the blast and slice us like fruit. The lessons came with cartoon turtles and slogans. Bert the Turtle taught us to hide under our desks while, somewhere in our imagination, the horizon lit up. Watch for yourself.

Even then, something felt wrong. We were children rehearsing for the end of the world. And everyone pretended it was normal.

The bomb wasn’t a museum artifact. It was atmosphere. It was baked into the news, the maps, the politics, the television. It was the logic behind the arms race, the architecture of fear. The Cold War was never cold in our minds. It was smoldering beneath our lunchboxes and morning announcements.

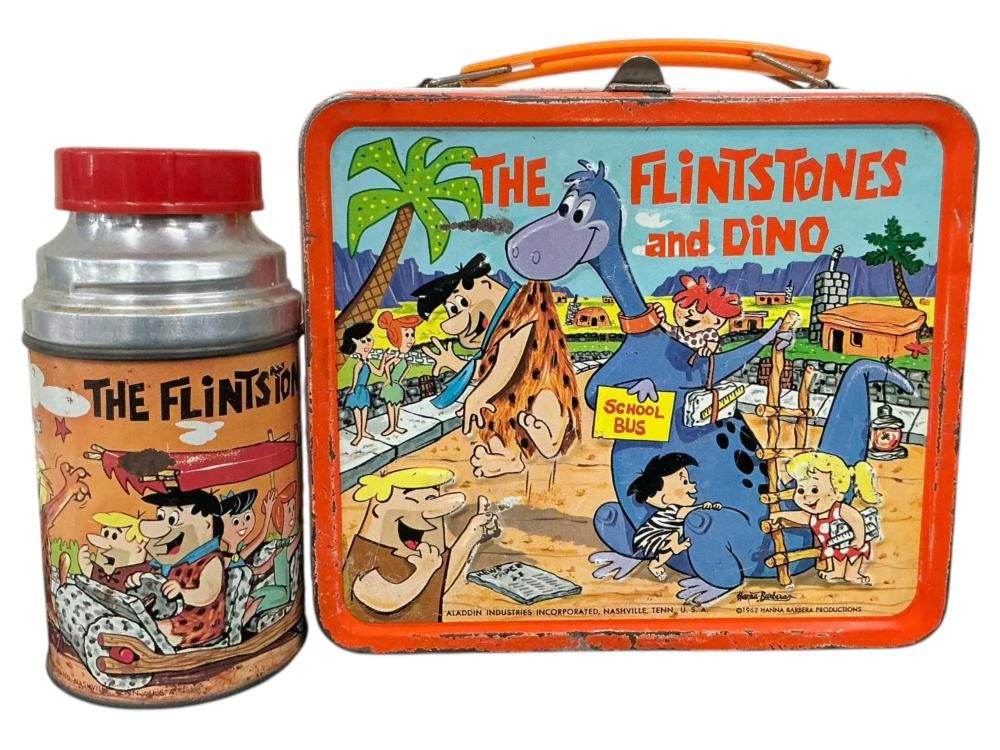

The Flintstones was on primetime TV and we watched it. I had a Flintstones lunchbox. Perfect when living in a time when we could all be bombed back to the stone age.

America had emerged from World War II triumphant and trembling. We had dropped the bomb, twice, and in doing so, inherited a power we barely understood. There was celebration, yes—flags waving, victory parades, the mushroom cloud sold as progress. But underneath, there was something else: the knowledge that we had built a god out of fire, and we didn't know how to put it away.

Operation Crossroads was the rehearsal for the rest of the century. And now, in 2025, that rehearsal still echoes. We speak casually of "tactical nukes" and "limited strikes," as if such things could ever be contained. We rattle the saber, point fingers, draw red lines with invisible ink. All the while, the planet itself groans beneath the weight of past decisions.

I live now not far from Los Alamos, where the bomb was born in secrecy and silence. Down the road from Durango, where they mined uranium from the red dust and fed it into the war machine. Some of that dust never settled. It rides the wind still, seeps into rivers, burrows into bones. People here live with cancer clusters, contaminated wells, and unspoken history.

And still, we pretend it was all necessary. That we were the good ones. That the price was just.

But what has it meant, really, to live under this shadow? To carry this knowledge in the body, like an inherited ache? For me, it meant learning to question the official story. It meant an early awareness that safety was often an illusion, and that authority rarely came without cost. It meant cultivating a deep desire for beauty, for creation, for slowness—as a kind of antidote to the machinery of erasure.

It also meant paying attention to silence. To the spaces between headlines. To the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who rarely spoke. To the islanders of Bikini Atoll, displaced and poisoned so the U.S. could practice ending the world more efficiently. To the land itself, which remembers everything.

The short snorter in my drawer isn’t just a piece of paper. It’s a portal. A question. A mirror. What do we sign our names to? What do we inherit? And how long until we wake up from the dream that control and destruction are the same thing as power?

I think now of children practicing lockdown drills in classrooms, not unlike the ones I crouched in sixty years ago. Different threat, same ritual. Same tightness in the chest. Same lie that hiding will save you.

We need new rituals. Ones that begin not in fear, but in reckoning. Not in posturing, but in presence.

The Atomic Age is not behind us. It is within us. Etched into our policies, our landscapes, our imaginations. And unless we choose to truly understand what we have done—and what we are still doing—we will remain asleep at the switch, dreaming of fire.

I unfold the short snorter one more time. I read the names. And I do not judge them. But I do remember.

And that, perhaps, is where healing begins.

Way older than you, and remember the photos that came out after the bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Terrified me. I didn’t want to be a shadow on the sidewalk. And I lived in Chicago, and there’d be images in the newspaper with concentric circles showing how the bomb dropped on Chicago would effect us and we lived at the edge of the center circle. Terrifying. Not too long ago, I did a woven map piece with embroidered circles as a memory piece. Fear of the Bomb, like children now with fear of an active shooter. Oh, we humans.

Interesting reflection, esp. for those of us who are the same age... I remember those drills and have also contemplated the similarity to today's school drills, although I see (saw) them as a way to manage fear. The last line about not judging is a strong and necessary statement to include in healing.