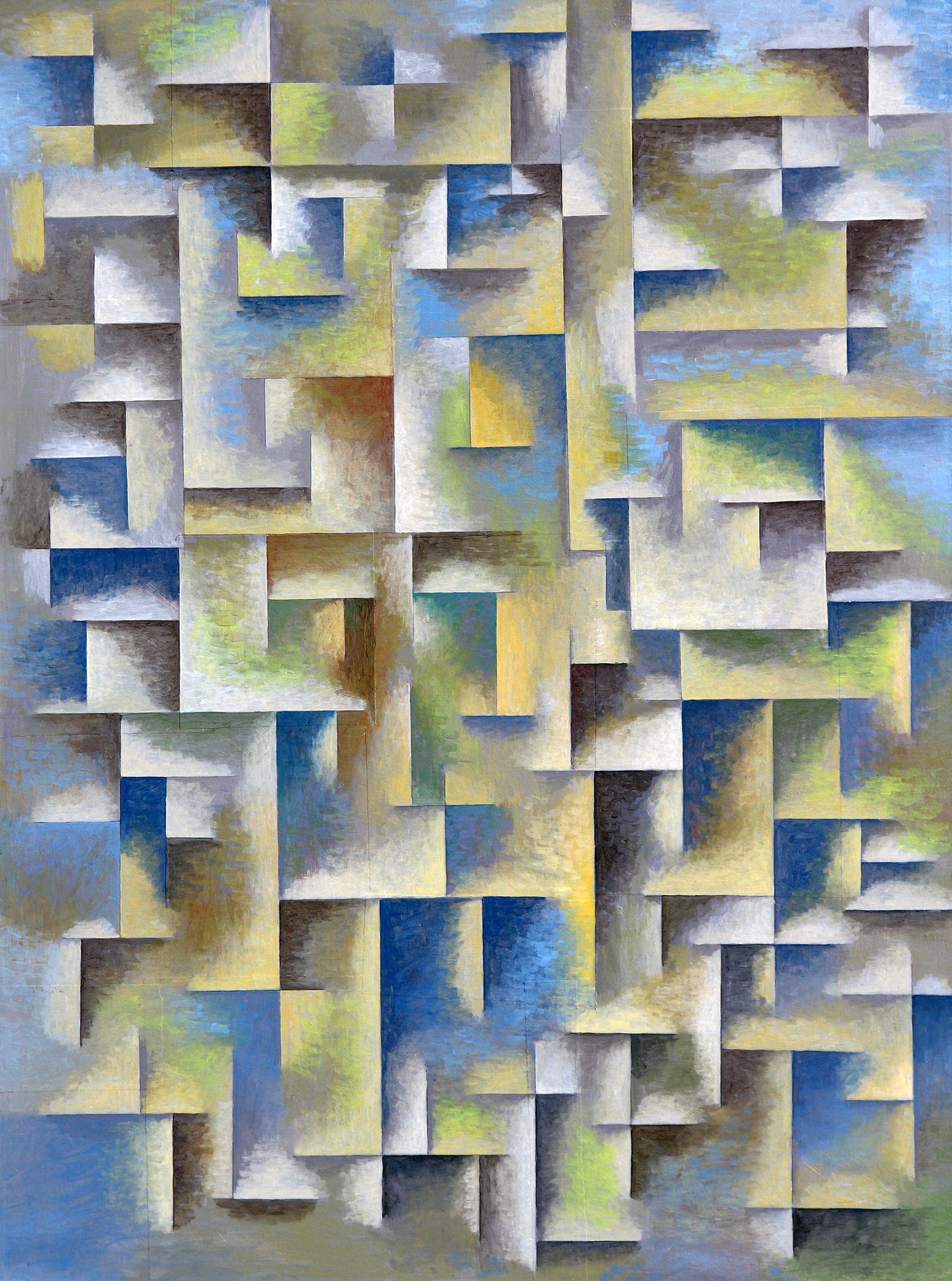

Above, another painting experiment of mine exploring the single motif of perpendicular strait lines as the compositional element as in the previous article 'Passage' and Visual Dynamics.

Push and Pull in Analytical Cubism: The Visual Musicality of Form and Space

The concept of "push and pull" in Analytical Cubism can be described in terms of visual musicality, where the painting becomes akin to a musical composition. Just as a musical piece uses rhythm, harmony, and contrast to evoke a sense of movement and emotion, Analytical Cubism employs the dynamic interplay of planes, tones, and lines to create a rhythmic flow that guides the viewer's experience. This visual musicality, orchestrated through the push and pull of elements, turns a painting into an experiential journey, much like listening to a piece of music.

Rhythmic Fragmentation and Layering

In music, rhythm is created by the repetition and variation of notes, while in Analytical Cubism, rhythm is generated by the repetition and variation of fragmented forms. The fractured representation of subjects in Analytical Cubism has a rhythmic quality that can be likened to musical notes being played in a sequence. Each facet of an object, whether it be a violin, a guitar, or a human figure, acts like a musical phrase that is repeated, varied, and interwoven to create a composition that is rich with movement.

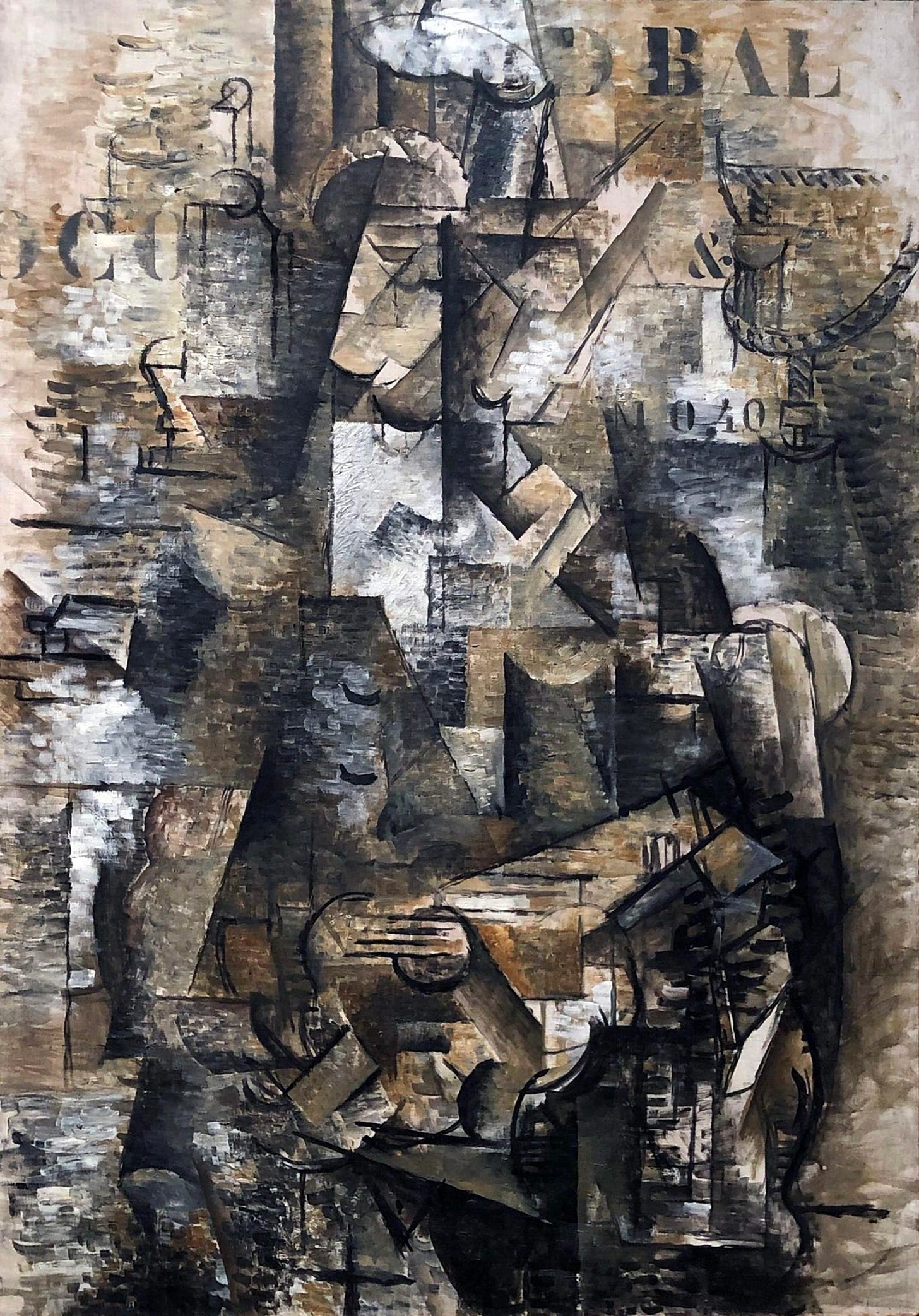

The interplay between advancing and receding planes establishes a rhythm of push and pull, where some shapes move forward, while others fall back, creating a visual cadence. This rhythmic flow can be observed in works like Braque's Violin and Candlestick (1910), where the repeated motifs of violin parts, fragmented and layered in different planes, evoke a sense of visual syncopation. The overlapping planes create a staccato effect, much like a series of musical notes played in quick succession, providing a lively, dynamic visual experience.

Harmonic Relationships and Tonal Variations

In music, harmony is created by combining different notes to produce chords that resonate with each other. Similarly, Analytical Cubism creates visual harmony through the relationship between overlapping planes and tonal variations. The limited palette of browns, grays, and ochres used by Braque and Picasso serves as the tonal foundation, while the subtle variations in light and dark create a visual harmony that echoes the concept of musical chords.

The push and pull effect in Analytical Cubism can be understood as a harmonic interplay, where the contrast between light and dark planes evokes a sense of depth and resonance. Lighter planes seem to advance toward the viewer, while darker planes recede, creating a harmonious balance akin to the interplay between high and low notes in a musical composition. This harmony is not static but dynamic, continuously shifting as the viewer’s eye moves through the composition.

In Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910), for instance, the tonal modulation between the different facets of the subject's face and body creates a sense of depth that feels almost melodic. The movement from lighter to darker tones has a flow that mirrors the movement of a melody, rising and falling in intensity, thereby producing a sense of visual musicality.

Counterpoint and Dynamic Tension

The concept of counterpoint in music refers to the relationship between two or more independent melodies that interact harmoniously. In Analytical Cubism, the juxtaposition of multiple perspectives and fragmented planes creates a visual counterpoint—a dialogue between different viewpoints that contributes to the overall sense of movement and depth. Each plane, with its own direction and tonal value, acts as an independent visual element, yet all the planes work together to create a cohesive composition.

The push and pull effect is central to this visual counterpoint, as the overlapping planes seem to be in constant dialogue with each other. Some planes push forward, while others recede, creating a dynamic tension that is reminiscent of musical counterpoint, where different melodic lines converge and diverge to create a rich, layered experience. This interplay of opposing forces brings a sense of vitality and complexity to the painting, much like the simultaneous melodies in a fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach.

In Braque's The Portuguese (1911), the fragmented forms of the figure and the background create multiple points of focus, each vying for the viewer's attention. The result is a complex visual counterpoint, where different planes and perspectives interact to create a sense of movement and depth. This interaction of forms, advancing and receding, produces a dynamic tension that can be likened to the interplay of independent melodies in a musical composition.

Visual Tempo and Viewer Engagement

Tempo, the speed at which music is played, also finds its counterpart in Analytical Cubism. The fragmented nature of Cubist compositions creates a visual tempo, with the push and pull of planes setting the pace at which the viewer's eye moves across the canvas. Faster, more abrupt transitions between planes create a sense of urgency and movement, while slower, more gradual transitions create a more meditative experience.

Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin (1910) exemplifies a slower visual tempo. The fragmented planes are arranged in a way that allows the viewer's eye to move more leisurely through the composition, lingering on each facet before moving on to the next. This slower tempo creates a contemplative experience, inviting the viewer to explore the depth and complexity of each plane and how it relates to the whole.

Conversely, in Braque's Violin and Palette (1909), the sharp angles and abrupt shifts between planes create a faster tempo, with the viewer's eye quickly moving between advancing and receding elements. This rapid movement generates a lively, energetic visual experience, akin to the brisk tempo of an allegro movement in a musical composition. The push and pull in this work is dynamic and immediate, with the overlapping planes creating a sense of urgency and excitement.

Crescendo and Visual Climax

The idea of a crescendo—a gradual increase in intensity—is also present in Analytical Cubism. The interplay of push and pull can create a visual crescendo, where the intensity of the composition builds to a climax, much like a piece of music gradually increasing in volume and complexity. In Analytical Cubist works, this crescendo is often achieved through the accumulation of overlapping planes and the interplay of light and dark.

As the viewer moves through the painting, the push and pull of the planes create a sense of progression, leading to a visual climax where the forms become most concentrated and dynamic. This crescendo effect can be seen in works like Braque's Woman with a Guitar (1913), where the fragmented planes become increasingly dense and complex around the central figure, creating a focal point that serves as the climax of the composition. The visual intensity builds as the viewer moves toward this central area, much like the swell of a musical crescendo.

Visual Syncopation and Disruption

Syncopation, a technique used in music to create unexpected accents by shifting the rhythmic emphasis, can also be seen in Analytical Cubism. The push and pull of fragmented planes create a visual syncopation, where certain elements seem to unexpectedly advance or recede, disrupting the viewer's expectations and creating a sense of surprise. This visual syncopation adds to the dynamic quality of the composition, keeping the viewer engaged and attentive.

In Picasso’s Ma Jolie (1911-1912), the fragmented forms of the figure are arranged in such a way that certain planes seem to suddenly push forward, while others recede, creating a sense of visual syncopation. This disruption of spatial expectations mirrors the use of syncopation in music, where unexpected accents create a lively, unpredictable rhythm. The push and pull in this work is not uniform but varied, with each plane contributing to the overall sense of movement and rhythm.

Conclusion: The Symphony of Analytical Cubism

The visual musicality of Analytical Cubism, achieved through the push and pull of planes, tones, and lines, transforms the act of viewing into an experience akin to listening to a symphony. The rhythmic fragmentation of forms, the harmonic interplay of tonal values, the dynamic counterpoint of multiple perspectives, and the visual tempo set by the advancing and receding planes all contribute to a rich, layered composition that engages the viewer on multiple levels.

Just as a musical composition uses rhythm, harmony, and contrast to create an emotional experience, Analytical Cubism uses the push and pull of visual elements to create a dynamic, multi-dimensional space that invites the viewer to engage, explore, and interpret. This visual musicality is what makes Analytical Cubism not only a groundbreaking artistic movement but also a deeply resonant form of expression, where the push and pull of elements create a visual symphony that continues to captivate and inspire.