This is a companion to On Creating Without an Audience.

On Vanishing Works and the Art of Leaving Traces

Journal Entry: November 6, 2025

Every artist eventually learns that most of what we make will not last. The archives of history whisper it plainly: almost all of the art of every generation is lost. Paint flakes, paper decays, hard drives crash, galleries close, heirs forget, archives are dispersed, wars and floods sweep through the world. Everything is lost in the deluge of everyone’s busy daily lives.

Even in well-preserved collections, perhaps only three to fifteen percent of holdings are ever displayed. The rest sleep in darkness. It is sobering to know that what we produce today may never reach tomorrow.

Yet this fact need not cast a shadow over our practice. It can, instead, clarify the nature of what we are doing. The disappearance of art is not failure - it is the material truth of time in an infinite expanse. Each work is a brief configuration of matter and meaning. To create with that awareness is to enter into right relation with impermanence, to honor the rhythm that holds all things: birth, unfolding, dissolution.

When an artist makes peace with transience, a quiet freedom appears. The anxiety of legacy begins to dissolve. One no longer works to impress eternity, but to participate consciously in the ongoing moment by moment stream of creation. The goal becomes presence, not permanence.

Still, there is value in what I would call archival consciousness. It is a discipline of care, not a chase after immortality. Archival consciousness means leaving the future a few clear traces: photographs, documentation, dates, materials, notes, context. It is a way of saying, I was here; this is what I saw. The impulse to preserve is not vanity - it is hospitality toward those who may one day look back. But the mature artist prepares carefully and then lets go.

History tells another truth: from the vast field of what is made, only a narrow thread becomes remembered as the canon. Each century, each decade even, produces thousands, tens of thousands of worthy voices, but only a small constellation is later woven into the official narrative of art. This is not simply because of quality, but because only so much can be collected, and within that collection, only so much can be carried forward as representative of a period. The canon, then, is not the sum of greatness; it is the residue of survival shaped by chance, access, and later interpretation.

Future generations, looking back through the narrowing tunnel of what remains, decide what appears central. Often this happens long after the artists are gone. A movement dismissed in its own time may later be seen as prophetic. Another once-celebrated style may fade to a footnote. What we call importance is a moving target - an artifact of what the future happens to find legible and relevant. To become canonical is as much a matter of temporal luck as of talent.

And yet, each generation, whether or not its members become canonized, continues a vast conversation that began centuries ago. Every brushstroke, every poem, every song is a reply to something said long before we arrived on the scene, and an offering toward what has yet to be spoken. We are inheritors of countless unfinished proposals. Our task is to listen carefully and add our voice in such a way that the next ones to come after us may hear an echo and respond. Some among us will find their works carried into the future’s conversation - quoted, reinterpreted, transformed - while others will speak only to the present moment. Both are necessary. Both sustain the trans-temporal dialogue and the maintenance of the community.

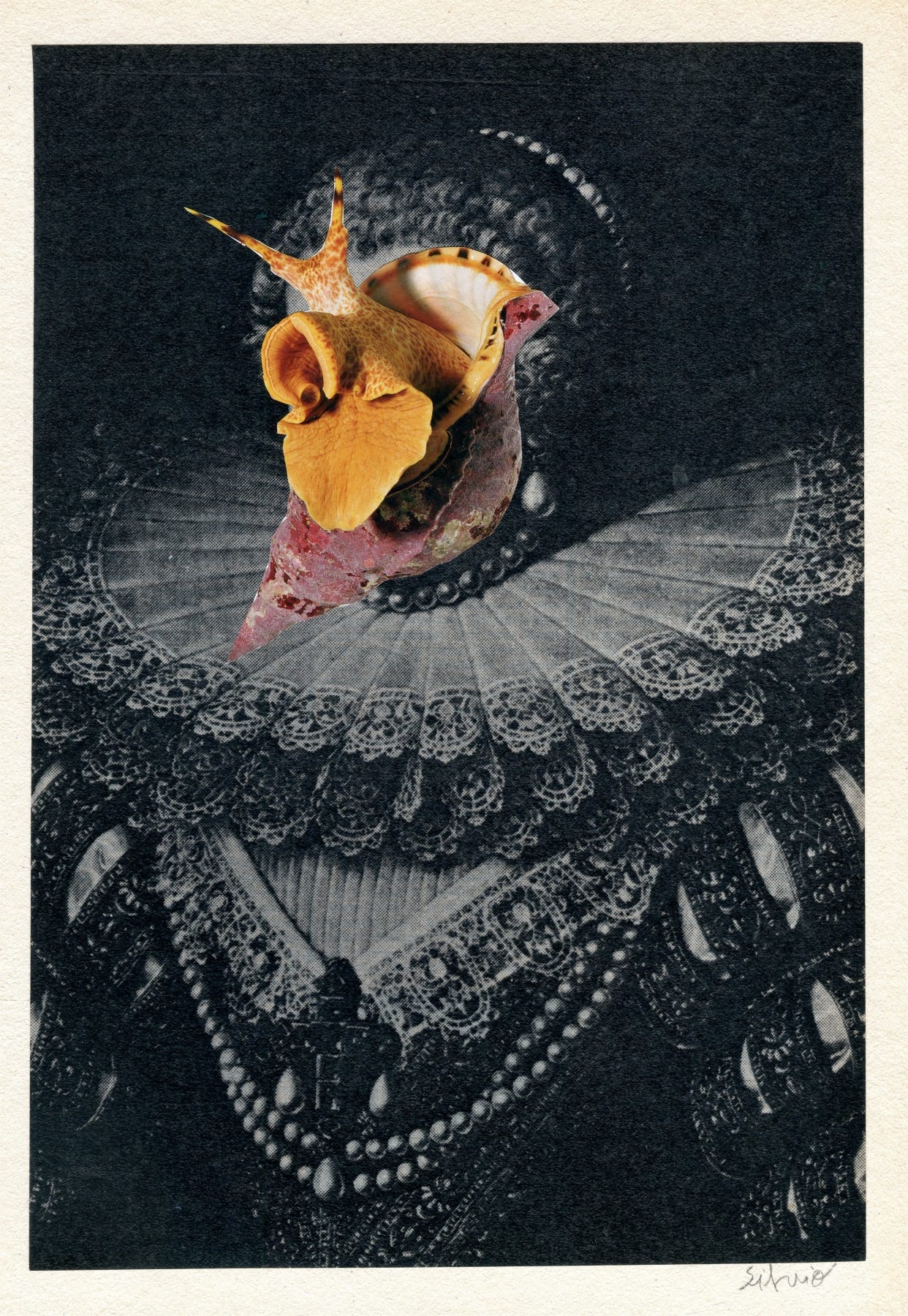

Perhaps the wiser metaphor for our work is not the building of monuments but the planting of seeds. Every work carries its potential forward. Some seeds may never sprout; others may reappear generations later in new soil, transformed. A forgotten collage might inspire a future artist’s experiment, or a line from a notebook might resurface as a fragment of someone else’s revelation. This is survival by resonance rather than merely storage.

Preservation, then, becomes a collective act. None of us can carry our own archive alone. We depend on each other - the communities, cooperatives, and small independent institutions that act as memory vessels of our time. By documenting and safeguarding one another’s work, we extend the field of remembrance beyond the solitary ego. In this sense, to archive is a form of love.

And there is a deeper humility yet: the understanding that the future will curate us. Posterity will decide what to keep, what to reinterpret, and what to let return to dust. We cannot choose our work’s afterlife. But we can shape the signal we send forward - the clarity of our intent, the distinctiveness of our vision, the authenticity of our voice and the context in which we lived. These qualities travel further through the noise of centuries than we might imagine. It is the record we leave for those who wonder which is the way to go forward.

When we accept that most of what we make will vanish or be scattered to the wind, what remains acquires new intensity. The studio becomes a site of presence, not possession. The artwork becomes a conversation within the larger field of impermanence, a gesture toward beauty that knows it will one day be gone. We may not preserve the work, but the work preserves something of us: the way our spirit moved through the world.

Perhaps that is enough.

To leave traces, not monuments.

To seed the unseen gardens of the future.

To add one clear note to the endless conversation of art.

I live both in the here and now as well as looking into the future but I don't spend much time planning or seeing what will be or even having much of an idea of what will be there. Just like the items I find to use in my assemblages (old, forgotten, used, rusty, tarnished, unusable as once was etc), the new life I give these things in my art may someday be reused once again in someone else's art or whatever. It's why I love junk and thrifting and picking up cast off stuff I find along my daily comings & goings. Hell, I'll be dead and gone and no way of caring what happens to my art. I suppose my kids will do what they want with it, give it away, find a place to sell it.........whatever. I don't and won't dwell on what will happen to it all as I won't be around to give a damn. There'll be no pyramids built to house my body along with all my stuff. I won't even leave a body as I'll be turned to ashes and dumped somewhere. In the here and now is what I'm concerned with and being in that Zone when I create that's benefiting me NOW. Having been given the gift of life 68+ years ago is a privilege, an honor, and greatly appreciated and I want to do/give/make what I can while I can still breathe and move. Another great article, Cecil. Thankyou.

Great article Cecil. Reminds me of our late friend, Ed Benson, who deliberately destroyed his paintings-perhaps as a sign of his art's impermanence. He always seemed to be thinking 3 steps ahead of everyone else. This also reminds me of those Buddhist priests who create elaborate sand art over several days, and then destroy the work immediately afterwards. Also a sign of change and that nothing lasts forever. Only perhaps your memory of the event. Certainly food for thought.