Between Floors: The Artist as Elevator Operator

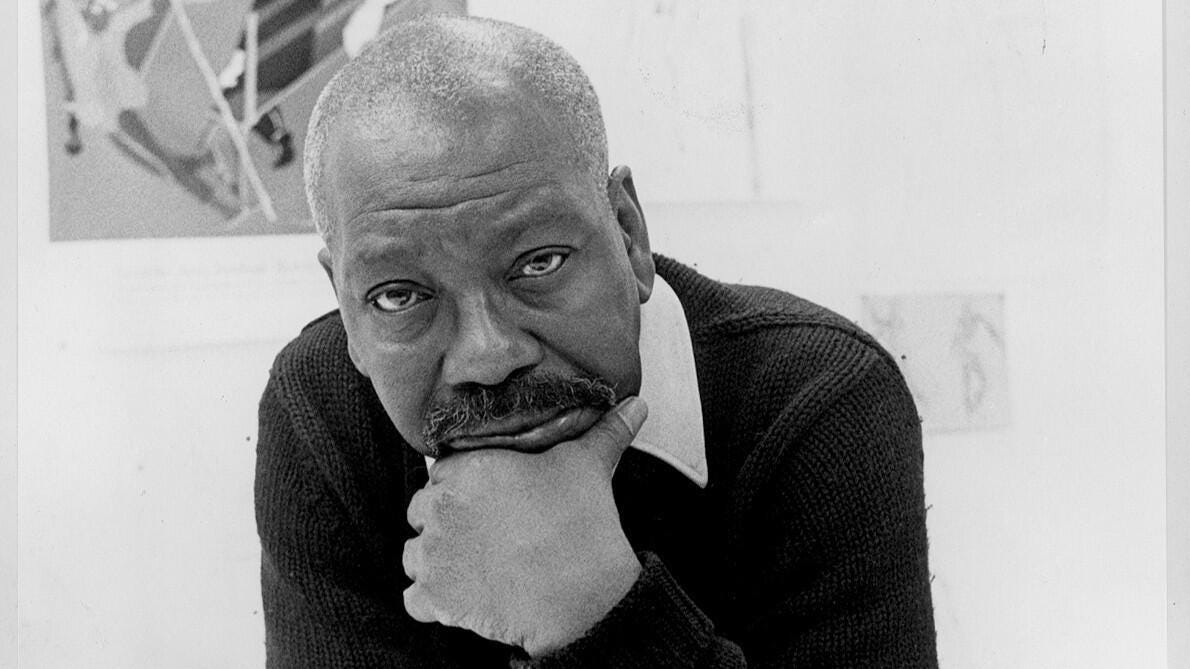

It’s easy to forget that even the most celebrated artists once occupied quiet, often invisible places in the world—spaces where they observed more than they acted, waited more than they produced. Consider this: Jacob Lawrence, Robert Rauschenberg, and Sol LeWitt—three artists who helped shape American art in the 20th century—all worked at one point as elevator operators.

Think about that for a moment. The elevator shaft—a narrow vertical corridor between the heights and depths of a building—is a kind of metaphor for the early life of the artist. You ride between levels, watching others get on and off, coming from one story, heading to another. You’re moving, yes, but in place. Watching. Listening. Waiting.

Jacob Lawrence, operating an elevator in Harlem during the 1930s, wasn’t just earning a paycheck. He was absorbing life—faces, gestures, snippets of conversation. That neighborhood became the pulse of his Migration Series, a masterpiece rooted in movement, history, and rhythm.

Robert Rauschenberg, navigating the clunky lift of a New York building, likely collected fragments of urban life—not just in objects, which he famously embedded into his art, but in impressions: a voice shouting from a hallway, a scrap of paper on the floor, the accidental poetry of disorder.

Sol LeWitt, stationed at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1950s, stood quietly in the mechanical cage while some of the greatest artworks of the time hung just a floor or two away. Imagine being suspended in that in-between: part observer, part ghost, part pilgrim just outside the gates.

There’s something profound in this. Not just in the humility of such jobs, but in what they offered: time to observe without being observed. Time to think. To notice. To gestate ideas in stillness. The elevator operator is the hidden witness, the silent ferryman of the vertical city, the one who knows what’s on every floor without belonging to any of them.

And isn’t that, in some way, the artist’s task?

To pass through the layers of the world, watching how people move from one space to another. To understand the architecture of society from inside the shaft. To rise and fall and see what others miss in their rush to get somewhere.

If you’re still working your version of the elevator job—something unglamorous, repetitive, even thankless—don’t discount it. These quiet years may be your apprenticeship in attention. Your proving ground for patience. Your secret library of images and insights. What matters is how you use that space. What you carry from floor to floor. What you see in the time between arrivals.

Sometimes, the most important part of becoming an artist is learning how to stand still—while everything else moves around you.

For these studio artists there was a secret purpose. The choice to take a job like elevator operating wasn't just out of necessity—it was strategic. These were jobs that demanded physical presence but minimal physical, mental or emotional output, leaving the artist's true energy conserved for the studio. Unlike a high-stakes office job or a physically exhausting shift, riding an elevator up and down for hours allowed the inner world to keep humming. The mind could wander. Ideas could percolate. The creative self remained intact, unspent. In this way, such work was not a distraction from art, but a quiet break from the studio and a protector of creative energy—a low-cost, low-conflict harbor that left the artist’s most vital resource, attention, available for what really mattered.

And not only that, such a job will not confuse the issue as to why you are working that job; to serve the studio. It is not competing to be your life’s work.

Yes, to having a job that doesn’t leave you drained, so you have the mind space you need. Most of the jobs I had, & I had lots, required me to be present. Really present. There was nothing left of me often to create in a physical space, but one job required a lot of driving all over the state! So boring on long stretches of road, and oh the things i could make in my mind. Thanks for these posts.

This reminded me of the best cruddy job I had. I worked at the Sacramento Airport in the parking toll booth when I was getting my teaching credential. It was set on a huge tarmac out in the middle of rice fields and lots of sky. I used to study out there. It was very peaceful. I could do my homework there because I would have several hours to kill in between cars. When the cars were exiting I used to do little human behavioral studies. I found out we humans are very much alike. How many people used a money clip, how many people used a wallet, how many people pulled wadded up money out of their pockets? Some days were red days (colors of people’s’ clothing), some were blue, etc. how many cars had broken electrical windows where they had to open their doors to give you money. It was sometimes boring and sometimes it was interesting but I ended up getting my credentail with ease.