Sometimes works will sit around in my studio for extended periods of time while I slowly work on them or put them off to the side to consider later. While just registered into inventory, the above image and three more were made last winter. These works would fall under the category of Synthetic Cubism. I put them off to the side to think about them and consider expanding the set. I may do that but I thought I should go ahead and call them finished, photograph them and put them into inventory. Last winter I was studying Cubism in more detail after being excited about the brilliant exhibition Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition. I wanted to go to the exhibition but instead I bought the catalog and walked through the show with the exhibition’s curators Emily Braun and Elizabeth Cowling this video.

Back in the day, Cubism spread around Europe fairly quickly because it was the new thing coming out of Paris - the center of the contemporary art world at the time. Cubism was pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who transformed the art world with their revolutionary approach to form, perspective, and representation. Emerging in Paris in the early 1900s, Cubism broke away from traditional techniques, rejecting realistic depiction in favor of fragmented, geometric abstraction. The collaboration between Picasso and Braque not only redefined the nature of visual art but also inspired a wave of dialog, experimentation and innovation across Europe, giving rise to numerous variations and interpretations of the Cubist style and its implications.

Cubism developed in two main phases: Analytic Cubism and Synthetic Cubism both of which are important to my own development as an artist. I am old enough that many of these artists were still alive and working as I came to age. Between 1907 and 1912, Picasso and Braque worked closely, exploring Analytic Cubism, characterized by the dissection of subjects into geometric planes. They were very much influenced by the work of Paul Cézanne’s retrospective exhibition which included 56 works in 1907 at the Salon d'Automne. More on this connection in a future article.

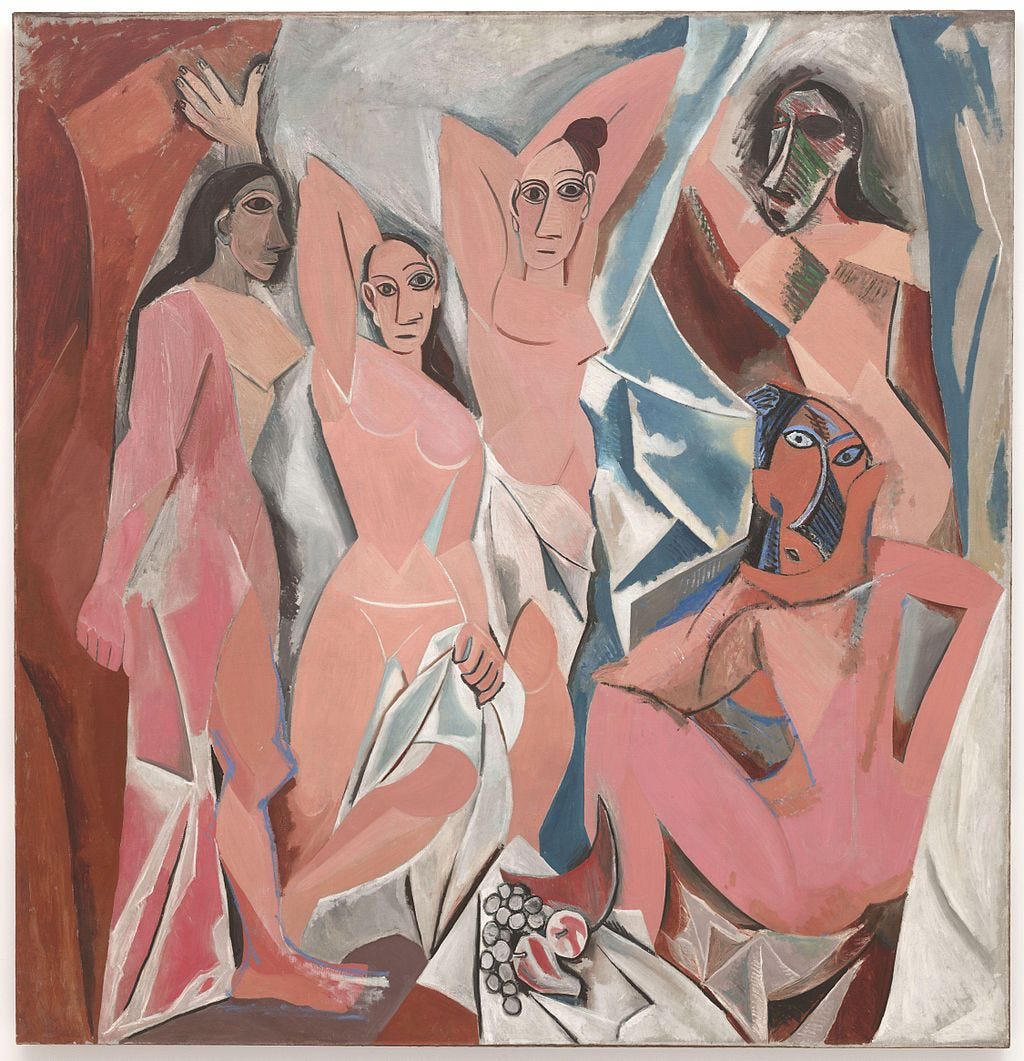

The works were more or less monochromatic with muted color, focused on deconstructing perspective and representing multiple viewpoints simultaneously through a tonal approach. They dissected still lifes, portraits, and landscapes into shards of shapes, creating a visual language that presented reality in a fragmented but more comprehensive form. Works exemplifying this period, emphasizing the intellectual engagement with form and structure over color or emotional expression including Braque’s “Violin and Palette” and Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon” (which some suggest is really pre-cubist and I argue was never finished. Picasso, having run into a problem he wasn’t quite sure how to solve, turned the painting to the wall for years while it slowly became legend by rumor with almost no one seeing it.) Meanwhile he went onto cubism proper.

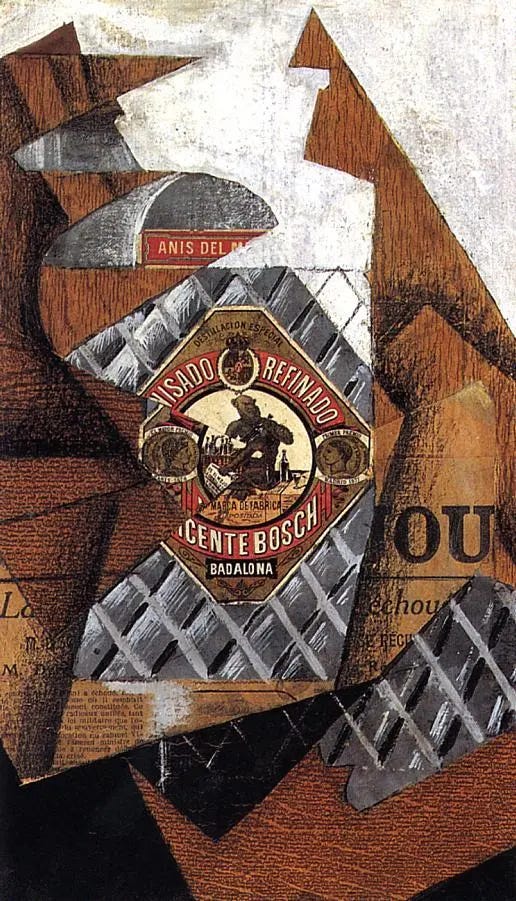

By 1912, Synthetic Cubism marked the second phase, incorporating collage elements, bright colors, and a greater emphasis on creating compositions rather than deconstructing them. My above work is based on a study of this period that saw Picasso and Braque introduce different textures and materials—such as newspaper clippings, wallpaper, and fabric—into their canvases, thereby blurring the lines between painting, drawing, collage. assemblage and sculpture. This approach gave rise to more playful and varied works, as in Picasso’s “Still Life with Chair Caning” and Braque’s use of stenciled letters. These collages questioned the boundaries of art at the time, challenging viewers’ expectations of what constituted a painting.

The spread of Cubism across Europe was facilitated by the vibrant cultural exchanges that took place in Paris, then a major hub of avant-garde art. Artists from around the continent visited or moved to Paris, where they encountered the Cubist movement and began incorporating its ideas into their work. The influence of Cubism extended beyond France to inspire movements like Italian Futurism, which adopted Cubist fragmentation to express dynamic movement and technology, as seen in the works of artists such as Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla. The Cubist language of intersecting planes and faceted forms resonated with the Futurists' desire to depict the energy of modern life.

In Germany, Cubism played a key role in shaping Expressionism and the development of the Bauhaus movement. German artists such as Lyonel Feininger and Paul Klee drew on Cubist techniques, merging them with their interest in abstraction and emotional resonance. The influence of Cubism is evident in their use of geometric shapes and their exploration of form and color as vehicles for conveying psychological depth. Cubism also informed the aesthetic of the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) group, which sought to express spiritual truths through abstraction, blending the analytical approach of Cubism with vivid, emotional expression.

Cubism's impact was not limited to painting; it also revolutionized sculpture, architecture, and design. Sculptors like Alexander Archipenko and Jacques Lipchitz applied Cubist principles to their three-dimensional work, creating pieces that played with voids, volumes, and intersecting planes, breaking away from traditional figurative sculpture. In architecture, the movement influenced modernist design, emphasizing simplified forms, geometric lines, and an integration of form and function. This Cubist-inspired sensibility laid the groundwork for the development of modern architecture across Europe, notably influencing Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus school.

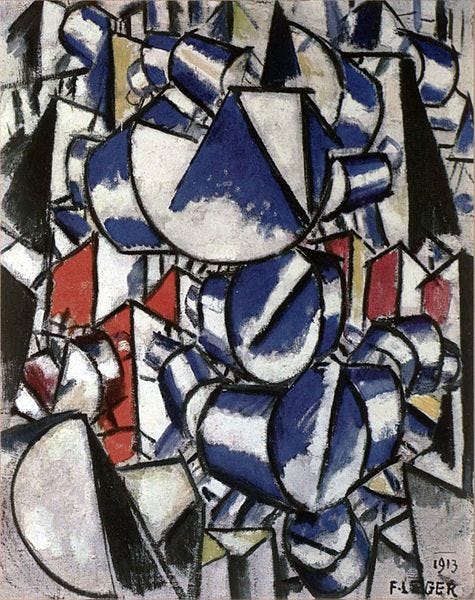

The First World War slowed the direct collaboration between Picasso and Braque (who went to the war and sustained a head injury), but by that time, Cubism had already spread widely and evolved into a pan-European phenomenon. It fostered the rise of new avant-garde movements and laid the foundation for abstract art in the decades that followed. Artists such as Juan Gris, who expanded on the Synthetic Cubist style, and Fernand Léger, who brought a more mechanistic approach to Cubism, further demonstrated the versatility of the movement and its adaptability to different artistic visions.

Cubism for me represents the starting point of abstraction and opened the question about what would abstract art represent? Kandinsky proposed that abstract art would be a visual expression for the eye like symphonic music is for the ear. This idea is at the root of what I have been thinking about and experimenting with my whole career.

Oddly, there are ubiquitous signs of musicality throughout Cubism in its motifs and in the way the images are constructed. Picasso however, did not want to accept the idea of pure abstraction. It made no sense to him…

In a 1928 interview, Picasso declared: “I have a horror of so-called abstract painting.…When one sticks colors next to each other and traces lines in space that don’t correspond to anything, the result is decoration.”

In 1935, the painter opined: “There is no abstract art. You must always start with something. Afterwards you can remove all trace of reality. There’s no danger then…because the idea of the object left an indelible mark.”

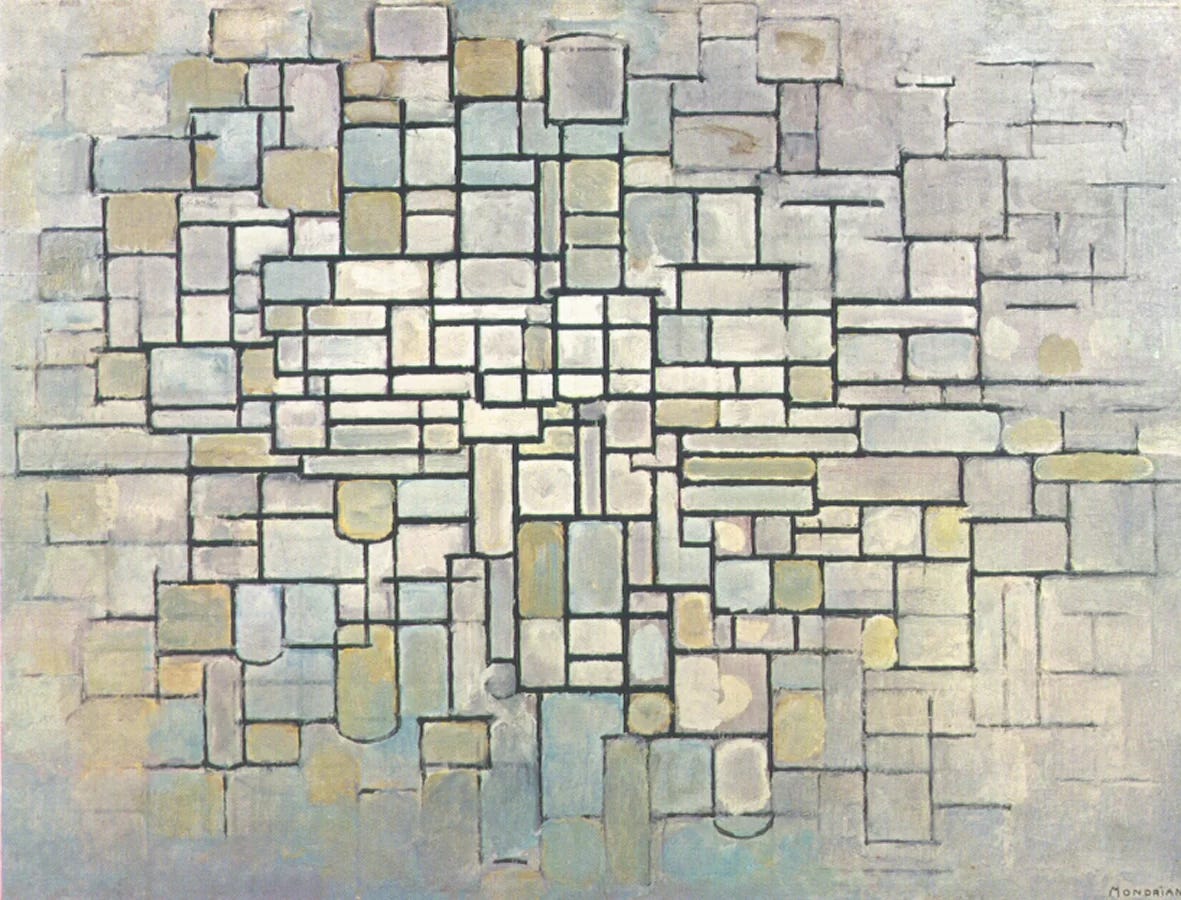

Piet Mondrian spoke publicly about the influence of Cubism on abstraction saying once that “Cubism did not accept the logical consequences of its own discoveries.”

My approach is based completely on the early modernists proposals that abstract art could be a visual version of music. I have published several books called Listening with the Eye. These are primarily experiments with asemic writing but bent away from poetry and toward music. I think of the spontaneous markings of asemic writing as if playing a pen or a brush like a musical instrument to capture body language, the language of the hand instead of literary language. Every drawing is like a recording of an impromptu performance on paper. A lot of these drawings are intentionally exploring musicality. I often study these drawings to pull out elements for paintings.

I have sketchbooks going back to 1977 that have the beginnings of my exploration of the idea. 2027 will mark 50 years of me thinking about and exploring visual musicality so I want to spend the next two years gathering together and laying out my thoughts on the subject as I continue working out the idea of symphonic painting - my lifelong pursuit.

Beautifully written article. I am reminded of Synesthesia.....where some individuals can smell and taste colors, see music, and other crossover senses of which is so fascinating and reminiscent of past acid trips that created similar affects. As a child I was so curious about the merging of such senses when I saw in some book I had about 'The Arts' where a cartoonist had interpreted what 'music' looked like, drawn out. The idea seemed so weird and radical, almost impossible to conceive and yet.....there it was, drawn out as it existed to the artist. In that black/white/gray painting you painted over that other piece, you really did capture that feeling of putting music in the visual sense that I could almost hear the music you listened to. I love this subject!